The French Consul General was looking over the guest list for his consulate’s Christian Dior show when he spotted a familiar name. It was the late 1950s and the diplomat was a denizen of Fifth Avenue, with its uniformed chauffeurs, white gloves and American aristocrats. He recognized the name not because the woman was social—she was decidedly not—but because she was his aunt by marriage. Huguette Clark, heiress to a $200–$250 million copper fortune (equal to about $3.4 billion today), occupied an entire floor of a Fifth Avenue apartment building, not far from the consulate.

The diplomat also knew she was a recluse.

“Look, she’s not going to come,” he told a Dior representative. “She’s my aunt, and she never goes out.”

The representative corrected him. “Oh, yes, she will. She wants to see the dresses. For her dolls.”

Clark, then in her fifties, was one of the wealthiest women in America. At first glance, she’d seem to be a member of a club featuring such swashbuckling, globe-trotting heiresses as Mabel Dodge, Peggy Guggenheim and the rich-by-marriage New York culture maven Brooke Astor. But unlike any of those ladies, Clark, a tiny blue-eyed blonde, was neither scandalous nor influential. She could have lived anywhere in the world, entertained lavishly in several mansions, and probably bought herself a new Latin lover every year. Instead, she chose to stay behind locked doors, building herself an intricate alternative universe out of dolls.

Clark did indeed attend the Dior show, as she would other French haute-couture shows in the 1950s. Arriving alone, she barely spoke. Few people remembered her. Later she would cable orders to Paris for scale replicas of the season’s styles to be sewn for some of her 1,100 dolls. They would have nothing but the best.

Antique French doll by Jumeau purchased in a pair by Clark for $30,000

Antique French doll by Jumeau purchased in a pair by Clark for $30,000

The elegant Huguette Clark was the younger daughter of a self-made Gilded Age mineral magnate named William A. Clark. She spoke with a touch of French on account of being born and educated in Paris. Her long life spanned the disaster of the Titanic (for which she had an unused ticket) to the falling of the twin towers. She’d been married once, in her early twenties, divorced and lived with her adored mother until her mother’s death, after which she became ever more homebound, associating mainly with her staff.

The massive—and meticulously dressed—doll and dollhouse collection that filled whole rooms of Clark’s vast Manhattan apartment was undeniably eccentric, but it was arguably not the most bizarre aspect of her life. Obsessed with privacy, Clark chose to spend her final two decades not in her Fifth Avenue apartment or her luxurious mansions in Connecticut and California but sheltered in a darkened 14-by-24-foot standard two-bed hospital room in New York City.

To be able to live in a hospital would seem a practical choice for someone with chronic health issues and deep pockets. Yet for the majority of the time she resided at Beth Israel Medical Center, Clark had nothing wrong physically. Her daily intake of medicine: a single vitamin.

Clark’s passion for privacy was such that her saga could have gone unnoticed by the world. But not long before she died, journalist Bill Dedman began to research her. Dedman’s eventual book, Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune, is being published this month, in time for the opening days of a trial scheduled to pit her legatees—a small number of caretakers and the foundation she established in her will—against distant relatives who are alleging that her will was obtained by undue influence and fraud.

Dedman discovered Huguette Clark while hunting for a house a few years ago. “I always enjoyed looking at the most expensive homes for sale,” he said, even though he wasn’t in the market to buy one. When he noticed a $24 million house on 52 acres called Le Beau Château in New Canaan, Connecticut—situated between houses owned by Harry Connick Jr. on one side and Glenn Beck on the other—he couldn’t resist the pull of curiosity. He drove over and poked around the ivy-draped stone walls that edged the estate. “I couldn’t see any house, just little caretaker cottages,” he recalled. “The caretaker came out and said he had worked there for 20 years and never seen the owner. I learned that no one had occupied it for 60 years. Then he asks me, ‘Do you think she’s still alive?’ And I thought, ‘News is being committed here.’ ”

Dedman eventually followed his nose to another of Clark’s “empty mansions,” an even more lavish and sprawling pile than the New Canaan property, called Bellosguardo, in Santa Barbara, California. With 21,666 square feet on acres facing the Pacific, and no owner seen on the property for decades, Bellosguardo was steeped in lore. Locals told stories of 1930s-vintage cars parked in the garage (true) and a table always set for dinner, Miss Havisham–style (false). The home’s mystery attracted even the Shah of Iran, who tried to buy it.

After learning the owner of these fabulous properties was an elderly woman living in a hospital in New York, Dedman connected with a distant relative of Clark’s, a second cousin named Paul Clark Newell Jr. (who went on to co-author Empty Mansions with Dedman). Newell told Dedman he spoke with the elusive woman frequently and that she was healthy and seemed sharp as a tack.

But some of Clark’s distant relatives think otherwise. This September, a jury is scheduled to hear arguments from lawyers of the relatives who say her will—leaving most of the wealth to charity, not family—should be thrown out. A jury will be asked to decide, essentially, whether Clark, who died in 2011 at the ripe age of 104, was non compos mentis.

But this is far from a simple question.

Painting of a young Huguette Clark

Painting of a young Huguette Clark

One must travel back to the 19th century to begin to understand the woman who lived at Beth Israel Hospital. The daughter of Clark’s young second wife, she was born in Paris—her parents lived on the Avenue Victor Hugo in the fashionable 16th arrondissement, hence “Huguette.” When she was 5, the Clarks moved Huguette and her older sister Andrée home to the biggest house in New York City, a six-story mansion overlooking Central Park with a special hideaway on the top floor in case an epidemic hit the city.

W.A. Clark was born in Pennsylvania and made a fortune mining in Montana, becoming a U.S. senator and a major art collector before his death. His first wife, with whom he had five children, died in 1893, after which he took up with a series of younger women, including Anna LaChapelle, who was around 15 when they met. He married her in 1901, when she was 23 and he was 62. Huguette was born in 1906.

Huguette adored her mother, and they lived together for decades in an apartment on Fifth Avenue at 72nd Street. Her attachment was so intense that when Huguette was hospitalized, well after her mother had died in 1963, she remodeled one of the bedrooms to be an exact replica of Anna’s. Although the work was completed at a cost of $400,000, Huguette remained in the hospital and never once saw the room in person.

Upon turning 18, Huguette inherited her portion of W.A. Clark’s financial fortune and went on to purchase real estate in New Canaan and Manhattan, also inheriting the Santa Barbara property when her mother died. Like her father, she was an avid art collector, especially of French Impressionists. But her real passion was dolls—and privacy.

W.A. Clark had weathered some very public scandals in his political life. Perhaps that explained his daughter’s shyness. In any case, Huguette’s desire not to be in the papers was so strong that when Citibank auctioned off a safe deposit box of millions’ worth of her mother’s jewelry without informing her, she refused to sue, according to Empty Mansions. Similarly, when someone stole a French impressionist painting—a Degas ballerina—and the oil turned up on the wall of tax man Henry Bloch’s living room in Kansas, she didn’t want the attention surrounding a retrieval, so she arranged a deal to keep the painting in its same location, asking only for a photograph so she could enjoy looking at it.

Her Fifth Avenue apartment, left empty for 20 years

Her Fifth Avenue apartment, left empty for 20 years

As she aged, Clark grew increasingly isolated, like a female Howard Hughes without the germophobia. A doctor called to her Fifth Avenue apartment in March of 1991 found her emaciated and wrapped in a filthy bathrobe, her face disfigured by untreated skin cancer. After several months in a hospital, she was pronounced cured, but she would never again leave Beth Israel Medical Center.

Some might view her behavior as a sign of dementia, but Dedman came to believe Clark’s lonely years of untreated illness and her choice to remain (even when cured) in a hospital room, for which she paid between $800 to $1,200 a night, had more to do with shyness.

“She is the Boo Radley of all Boo Radleys—if Boo Radley’s parents had been millionaires,” says Dedman. “She was skittish. I don’t think any diagnosis fits her. When she got into her eighties, she was living alone in this 15,000-square-foot space. The staff was dwindling. She didn’t do too well with new people, so she didn’t replace them. She had a staff of 12 and that went down to three, then down to one. She outlasted her doctors, and she wasn’t going to go out and find a new doctor. Then she got some skin cancers and went through a period where it was drastically untreated.”

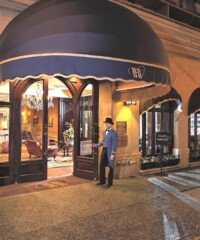

Beth Israel Hospital, where she spent the last decades of her life

Beth Israel Hospital, where she spent the last decades of her life

Once she had been moved to Beth Israel, her hospital bed was her command center: She communicated regularly with lawyers and other staff, oversaw her properties, corresponded by letter with friends around the country and in Europe and played with her doll collection by proxy, using employees to dress and maintain them.

Clark’s dolls and dollhouses were unlike any a child might collect. She avidly monitored Sotheby’s and other high-end auction houses for antique dolls, bidding tens of thousands by phone. Artists and workmen around the world designed domestic models to her exacting specifics, which she calculated based on readings of fairy tales and Japanese medieval literature.

“These one-of-a-kind tabletop models were texts, story houses, theaters with scenes and characters painted on the walls,” Dedman wrote. “And, like her father with his art collection, Huguette spared no expense. She commissioned religious houses with Joan of Arc, forts with toy soldiers, cottages with scenes from old French fables and house after house telling her favorite fairy tales: Rapunzel, the maiden with the long hair trapped in the tower. Sleeping Beauty, the princess stuck in sleep until a handsome prince awakens her with a kiss. Rumpelstiltskin, with the girl forced to spin straw into gold.”

Her collection grew so large it needed a full-time caretaker, and Clark eventually employed a middle-aged Brooklyn father to work five days a week organizing and overseeing the houses. This “man Friday,” Chris Sattler (who, like most everyone involved except the lawyers, refuses to speak to the media), was paid $90 an hour to create and catalog roomfuls of her 1,157 dolls and doll furniture. His special duty, though, was creating dollhouse scenes exactly as requested by the woman whom he and the rest of the staff always called Madame.

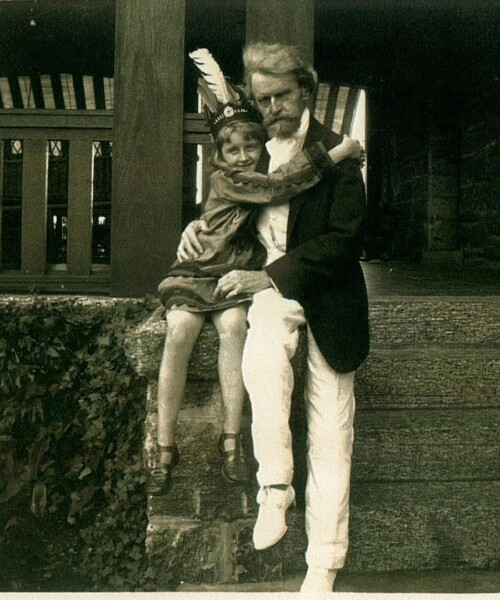

One of the rare photographs of the mysterious heiress, pictured here around age 37

One of the rare photographs of the mysterious heiress, pictured here around age 37

This was no mere child’s play, however. Sattler and others who worked for Clark came to regard the dolls as her form of art. When she was 58, Clark cabled a Bavarian artist who made and sold fairy-tale dolls: “Rumpelstiltskin house just arrived. It is beautifully painted but unfortunately is not same size of last porridge house received. Instead of front of house being 19 3/4 of an inch wide it is only 15 1/2 inch wide. Please make sure religious house has front of house 19 3/4 of an inch wide. Would also like shutters on all the windows. Would like another Rumpelstiltskin house with same scenes with scene where hay is turned to gold added as well as scene before hay is turned but with wider front and also wooden shutters on every window. With many thanks for all your troubles and kindest regards.—Huguette Clark, 907 Fifth Ave NYC.”

How seriously did the reclusive woman treat these fantastical creations? One of her former assistants told Dedman that Clark asked a craftsman to raise the ceiling on one of the dollhouses an inch or two, complaining, “The little people are banging their heads!”

“Her assistants will tell you that, and they see the look on your face and say, ‘No, no, no! You think she’s crazy and she wasn’t at all!’ ” Dedman said. “My co-author Paul talked to her on the phone for nine years, and he thought she was lucid as anyone else. She was not having any trouble telling fact from fiction. She recalled both that his granddaughter was taking ballet lessons and the tickets on the Titanic. She had a sense of humor. She kidded him about finding a girlfriend.”

Clark was especially fascinated with 18th-century Japan. She collected tiny dolls in historically precise costumes and employed a Japanese artist for the express purpose of going to temples and castles to do scale drawings. “Just as Americans would know a figure of Abraham Lincoln immediately from his top hat and beard, Huguette would know the figures from the Tokugawa shogunate, specifically those from the 1770s,” Dedman wrote.

In a deposition, Sattler told of how, when Huguette was 97 and lying in her hospital bed, she described six books in her collection on Japanese theater history, calling each one by title, even though she hadn’t seen them for years. “She was deep into a two-month project on Kabuki, creating a mock-up of a theater to be sent to the elderly artist in Japan, who would make a tabletop theater to her specifications,” Dedman wrote. Everything had to be perfectly to scale and historically accurate. Her written instructions were exacting for Sattler, who had received an undergraduate degree in history and literature from Fairfield University in Connecticut and then found himself, as Dedman puts it, “enrolled in the Huguette Marcelle Clark Graduate School of Japanese History.”

Sattler would follow her instructions—”Find all the ladies-in-waiting of medium size…. Find all the court ladies who are playing cards”—construct the scenes, take hundreds of snapshots of the figurines and scenery posed just so and deliver them to the hospital. Only after she approved the photographs would he assemble and bring the entire model to the hospital, for a few hours or a couple of days.

“Then she would be in heaven there for a while,” Sattler said in a deposition.

The second Jumeau doll

The second Jumeau doll

While she was alive—and even after her death in 2011—Clark was a woman of unyielding benevolence. She gave her nurse, Hadassah Peri, a Filipina immigrant, $30 million in gifts, property and cash, and bequeathed her an additional $40 million of her assets in her will. She reportedly gave $1 million in gifts to the night nurse who brought her warm milk to her hospital bed and sent $30,000 to a home health-care nurse she’d never met because she heard the woman took care of Clark’s stockbroker in his final years.

“This woman is home in Queens and Huguette’s lawyer shows up and says, here is a letter, but you must never tell anyone about it,” Dedman said. “She had this incredible generosity. She liked to give money to the people close to her.”

It is that very generosity that will be examined in the legal battle scheduled for September 17.

Clark specifically stated in her will that she had no connection to her family and didn’t want them to have any of her money. Instead she granted most of her fortune to a charitable foundation, which doesn’t yet exist, with other sizable bequests going to various caretakers involved in her life until the very end. The chief claimants in the lawsuit are grandchildren and great-grandchildren of her father from his first marriage, people she knew but who allegedly had not seen her in person for decades, and then only once at a funeral when some were still small children.

“The last time any of them were in her presence and talked to her was 1951,” Dedman said. “But that doesn’t matter. If they can knock out the will, they win. They are claiming that she was incompetent.”

For evidence, the claimants point to her obsession with dolls, her choice to live out her days in a hospital bed and the empty mansions themselves. What sane person would choose a darkened, small room instead of sumptuous estates with staff and landscaped grounds?

But relatives will have to explain other aspects of Clark’s later years that allude to her sanity. She “had lots of pen pals,” says Dedman, and wrote 4,000 pages of letters in French from her hospital room, in addition to overseeing properties and the exacting manipulation of dollhouse scenes. She had a niece she spoke with on holidays and a goddaughter on whom she doted (and who is included in the will). And Clark never told people she was living in a hospital, perhaps out of embarrassment, or to protect her cherished privacy.

New York lawyer John Dadakis, who represents Wallace Bock, Clark’s attorney and the lawyer who wrote her will, says he has ample evidence that Clark was of sound mind. “The record is replete with factual information as to Huguette Clark’s competency,” he told DuJour. “She continued to be up and about almost to the end of her life and those that saw her on a daily basis have indicated that she was fully competent.”

Among Clark’s occasional correspondents in the ’80s and ’90s was former Santa Barbara Mayor Sheila Lodge, who never met Clark but wrote back and forth to the heiress and her lawyers about Bellosguardo, local property improvements and other matters. Lodge knew Clark through letters and holiday cards—the latter without much imagery but densely packed with Clark’s “firm and distinctive” handwriting.

“She was a genuine eccentric as best I could tell, but she did not seem to be one bit short on her mental capabilities,” Lodge said. “She cared deeply about her place, although she hadn’t been here for decades. She had very specific directions about what should be done, and she called her staff here regularly.”

Lodge recalled that to the end of her life, Clark maintained ties to the community, where she held membership in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and belonged to the city’s Friends of Contemporary Art and Friends of Asian Art and was a charter member of the best golf club in town, although she never made an appearance.

“The jury will hear all this,” Dedman said. “And you can start a bar fight over it. Should the nurse have accepted $30 million? She has six houses herself now, one of them empty. People would say that’s over the line. But then you say, well, she worked for 20 years, seven days a week without a day off for a decade of it. And it’s very clear Huguette cherished her. If you say it that way, a jury would say she can give her money to anybody she wants.”

Dadakis points out that the 19 relatives objecting to the will prepared by his client in 2005 barely knew her. “Only one of the 19 had ever reached out during the period from 1991 through 2008 to speak with Huguette,” he says. “The others have indicated that they had no contact with her during that period and before.”

The attorney for the relatives, John Morken, did not return repeated calls for comment.

In the end, Dedman said his investigation could only go so far into the mind and motives of the recluse. He admits he never uncovered her “Rosebud”—the possible psychic wound that left her choosing isolation over society, and a hospital bed over a mansion. But he came to some surprising conclusions.

“She grew up in the biggest house in New York City, where you have money like water, where there was a different bathroom for every day of the month,” he says. “There’s a warping effect of such wealth. She’s shy and artistically inclined. Publicity was not good to her father. She got into a situation where she valued privacy more than she valued even her Degas when it shows up on a wall in Kansas. Imagine having a $10 million painting stolen and you won’t sue to get it back.”

More to the point: Imagine going to such lengths to hide from the world and then, after death, having your life examined in a media-filled courtroom. Because that is what is about to happen to Huguette Clark.

MORE:

The Secret History of the National Enquirer

10 Anecdotes of Excess About the Johnson & Johnson Family

The Astor Orphan Who Lost It All