One rarely drinks champagne alone. Whether that’s because of the sparkling wine’s still-strong reputation as a celebratory beverage, or more a matter of practical considerations—those little bubbles only last so long—it’s unusual, for most people, to pop a bottle sans amis.

So the situation in Hautvillers, the tiny village on the outskirts of Epernay, France, where Dom Pérignon recently premiered their 2004 vintage, was doubly odd. Not only were the assembled journalists and VIPs from around the globe first invited to sample the new champagne solo, they were instructed to do so in purpose-built clear plastic isolation booths—complete with piped-in piano music, a stem of snow-white orchids and a view of the very vineyards where the brand’s namesake, a Benedictine monk who helped popularize champagne in the late 17th century, grew his grapes. (It’s a measure of this writer’s immense sophistication that my first thought upon seeing the oddly pitiable-looking little plants was of the 1995 romantic comedy French Kiss, in which Kevin Kline plays an aspiring winemaker who enlists an unwitting Meg Ryan in his attempt to smuggle a single vine from Canada—Canada!—into his native France so he can use it to start a new vineyard.)

It was, truth be told, a bit tough to focus on the taste of the wine—or on anything, really, beyond a mild but persistent sense of embarrassment about being looked at by the butlers lined up in poses of attractive attentiveness nearby, and, perhaps, a not quite idle curiosity as to how long the oxygen within the transparent booths might last. Fortunately, fewer than 15 minutes passed before the drinkers were released from their zippered bubbles of forced contemplation and invited to imbibe a second glass of the 2004, this time in the presence of Richard Geoffroy, a former physician who has served as Dom Pérignon’s Chef de Cave since 1990. Responsible for overseeing the entire progression of the champagne from grape to glass, M. Geoffroy is naturally un peu proprietary about his product. “So far, it has been my wine,” he told the small U.S. delegation, “but now it is time to share. I was about to say that now it is yours, but I can’t stretch it that far. It’s ours.”

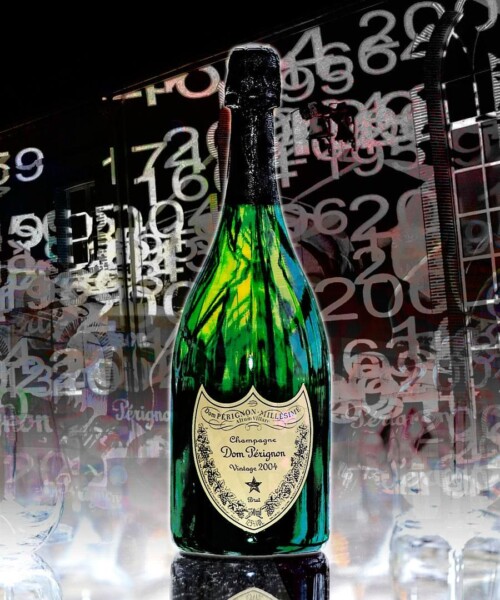

The “hallmark” of this particular vintage, he continued, “has been the ease.” Apparently, 2004 boasted nearly ideal weather conditions throughout the growing season, enabling him to create a Dom Pérignon that is “far more classical than any of the recent past.” (Many other brands of bubbly are non-vintage, or made from grapes grown during a few different years, precisely because it’s easier to maintain consistency that way. But for Geoffory, “Repetition is the enemy. These vintages are all so singular… being vintage is far more than positioning, for us.”) Certainly, the resulting champagne is delicious: Even one whose nose couldn’t quite detect the promised aromas of “almond and powdered cocoa” can attest to the vast gulf in quality between Dom P. and the no-name champagne we were given upon checking in to our hotel after a quick tour of the Moet & Chandon cellars in downtown Epernay.

That evening, Dom Pérignon hosted a six-course dinner at the historic Abbaye d’Hautvillers, which had the dual purpose of celebrating the launch of the 2004 and offering us yet another chance to taste it, this time in a slightly more typical context. By the end of a night in which the waiters seemed to refill the glasses every time anyone took a sip, the verdict was in: Magnifique. Only a single gripe was heard as the group filed towards the buses which would return them to their hotels, and it had to do with the fact that the free-flowing river of Dom Pérignon had finally come to an end.