If there were ever a person who might be able to clue you in on what life in a white-collar—or minimum-security or “country club”—prison was actually like, it was this guy. You know this guy. How many former New York City police commissioners, former overseers of Rikers Island, former consultants for U.S. security in Iraq or former almost-heads of the Department of Homeland Security are there in the world who ended up in the slammer?

I thought so too.

I wanted to find out what life was like for Bernard “Bernie” Kerik—what he ate, where he slept, who came to visit. But when I finally got to his prison in August of 2010, seven months into his sentence, I thought I was in the wrong place. After a convoluted five-hour journey that required trains and automobiles and the kindness of his pal John Picciano—a cop who worked as Bernie’s chief of staff both at Rikers and when he was police commissioner and remained so devoted that he had visited him in prison more than 60 times already—we pulled up to a building in western Maryland that looked like my high school. There wasn’t a single guard out front. No one searched us. There wasn’t even a metal detector.

I’d been to prisons before, almost all of them maximum-security and wretched; certainly none that looked like this. The Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland, has both medium- and minimum-security prisoners. Its visiting room is spotless and sprawling, with sparkling windows and walls that are decorated with quilts handmade by inmates.

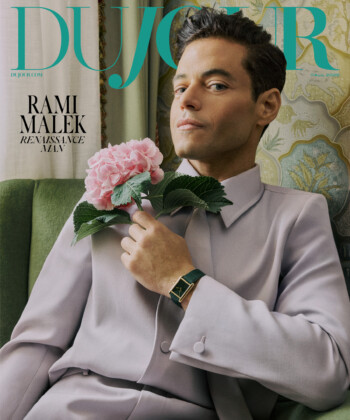

Enter Bernie Kerik, in moss-green khakis, matching long-sleeved button-down shirt and work boots, the outfit he would wear most every day for three years and 11 days. Kerik was the guy who previously ran one of the worst jails on earth (trust me, there are no quilts on the walls at Rikers) and the guy who was chosen by George W. Bush to be the head of the Department of Homeland Security, until it all hit the fan. First there was the illegal-immigrant-nanny brouhaha. Then the real dominoes fell. By November 2007, the former top cop was facing a 16-count indictment for, among other things, lying to the IRS and to the White House. He was also accused of accepting renovations to his home from contractors who wanted to work in New York. He ended up pleading guilty to eight charges, including tax fraud, in a plea bargain and was sentenced to four years.

Former New York City Police Commissioner Bernie Kerik, photographed in his New Jersey home

The last time I had seen Bernie, we shared an excellent Barolo and a couple of steaks at a fine joint in Midtown Manhattan. Like many journalists, I came to know him as the kind of dude who was forever entertaining, always plugged-in and seemingly invincible. Now he was in prison.

I visited him not even halfway through his incarceration. Already, he looked like a different man, and not in a bad way. He was working out like a maniac, jumping rope, running and walking four miles a day and doing anywhere from 600 to 1,200 push-ups. Bernie Kerik looked like a bull and was 50 pounds leaner. (By the time he was released in May at the age of 57, he was down 80 pounds from his pre-prison weight of 260.)

“So which quilt did you make?” I asked.

He gave me the look I deserved for that question. And then he laughed. I knew his spirit had not been crushed when I gingerly brought up the quilt topic again later and he lasered me with his green eyes (that just happened to match his prison outfit) and growled: “Enough with the fucking quilts.”

OK, so he was still Bernie.

And this was still prison.

But what I really wanted to know—what was life actually like on the inside?

Every time another big one goes away—Bernie Kerik or Bernie Madoff or Dennis Kozlowski (the Tyco guy with the $6,000 shower curtain) or Martha Stewart or Mickey Sherman (the once hotshot defense lawyer) or any of the Wall Street types who got busted in the recession—the inevitable questions arise: Did they go to Club Fed? To what the public perceives as “country club” prisons?

While there used to be a time when you could, in fact, find tennis courts at prison (specifically, the infamous now-closed Federal Prison Camp Eglin, which inspired the name Club Fed), “those stories were always exaggerated,” as CNBC’s John Carney wrote in a story on prison treatment. Plus, sentencing guidelines for “white-collar crimes” have only gotten worse for offenders, the result, as Carney noted, “of politics and public outrage largely tied to stock-market losses.”

NEXT: “That whole Club Fed mentality is complete nonsense.”