It all started with toffee. When Hawaii’s Tulsi Gabbard came to Congress in 2013, she sent boxes of her mother’s macadamia-nut toffee to each of the 434 other members—an aloha gesture if ever there was one. If that weren’t generous enough, she sent an additional 435 bigger boxes around for congressional staff. “Mom was stirring pots two at a time,” she says. For those outside the Beltway such sugary diplomacy might seem trivial, but it’s the kind of thing that can get a freshman representative noticed.

“I didn’t want to wait 20 years to get things done,” Gabbard says when I visit her cramped congressional offices, the type newbies are stuck with until they move up the ladder. “This was a small but important gesture, and I found members walking across the aisle asking, ‘Who is that Tulsi Gabbard?’”

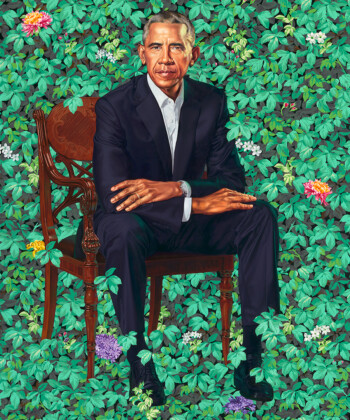

Tulsi Gabbard

Hawaii is not only America’s paradise but also its crucible of interracial harmony. It was the first “majority-minority” state, and almost one-fourth of current residents say they’re of mixed race. It’s where our current president was born to a Kansan mother and a Kenyan father. So it makes sense that Gabbard, the first Hindu in Congress—sworn in on the Bhagavad Gita—hails from Oahu and not, say, Omaha. Wholly Hawaiian, Gabbard, 33, still plunges into the ocean as soon as she gets home—“every time, without fail,” she says. She proudly surfs a 6-foot-1 shortboard and recalls that she resisted wearing shoes much of her childhood.

In Washington, Gabbard’s striking looks make her a standout against Congress’ tableau of white men in dark suits. Kyrsten Sinema, a young Democrat from Arizona, was impressed the first time they met, at an event honoring women leaders under 40. “She’s beautiful, of course,” Sinema recalls. “But I was struck by how calm she is, and super cool. She really represents her state.”

But Gabbard isn’t all gentle breezes. She’s making a name for herself on foreign policy and defense and finds herself at odds with her president. She’s an Iraq combat veteran, one of two female veterans in Congress now and one of just a few members of either gender ever to serve. When the Islamist group ISIS took over a large swath of Iraq this summer, Gabbard vociferously objected to President Obama’s idea to send hundreds of advisers to backstop the Iraqi Army. For Gabbard, who served in Iraq, the right number to send was zero—a position she says elicited no reaction from the White House but quiet “atta girl”s from her colleagues in the Democratic caucus.

Tulsi Gabbard

Given her interest in defense and foreign affairs, it’s no surprise Gabbard serves on the House Armed Services Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee, both befitting Hawaii’s large military presence and the island chain’s position in the Pacific. On a recent congressional delegation trip to East Asia, Gabbard impressed her GOP colleagues and went right to the Korean Demilitarized Zone, a bizarre place where South and North Korean troops are sometimes yards apart. That’s no small thing considering that Kim Jong-un has threatened to lob a missile into Hawaii. “In Honolulu we don’t see it as a situation of someone saying something crazy,” Gabbard says. “It’s very real.”

An interest in the military comes naturally to Gabbard. In 2004, she left her campaign for a second term on the state legislature and was deployed by the National Guard for a tour in Iraq. It was a transformative experience, in no small part because she saw firsthand the problems of women in the military. Gabbard also says that the military’s diversity made her more sensitive to individual rights and that she came back from Iraq supporting same-sex marriage—a topic she now has lengthy dinner-table discussions about with her family, including her state-senator father, who doesn’t share her views. Still, she says, “we hug at the end of the night.”

If Gabbard’s progressive move on same-sex marriage puts her in line with fellow Democrats, she’s also done plenty to reach out to Republicans. With conservative Rep. Aaron Schock she formed the Future Caucus, which focuses on issues that impact, or will impact, the millennial generation and attempts to solve these problems. “She’s an awesome person, and we’re great friends,” says Schock, who’s also Gabbard’s exercise buddy. “We came here to share problems and come up with solutions.”

Gabbard’s 6 a.m. workouts, long days and almost 10-hour commute home—which she makes at least once a month—mean little socializing outside of work. Instead of living in one of the Alpha Houses favored by representatives, she lives with her sister, a U.S. Marshal, and brother-in-law near the capital. There’s no dating and Gabbard claims not to partake in much of D.C.’s social scene. “I don’t have the time,” she says. “Not a single moment.”