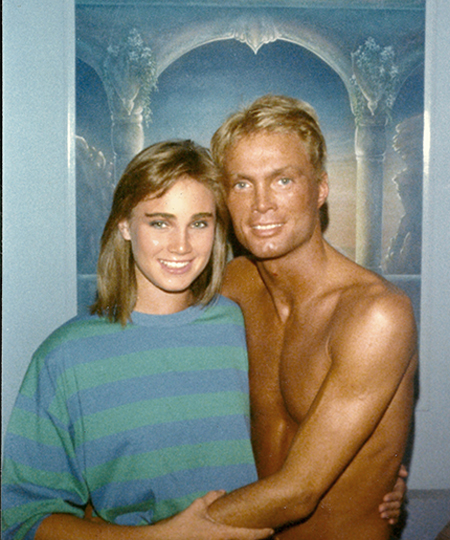

Heads turn as Hoyt Richards saunters through the low light and fashionable din inside the Petty Cash Taqueria, in Los Angeles’ Fairfax District. Six-foot-one with a chiseled jaw and a dimple, a forelock of gray-blonde hair cascading rakishly over one brow, he makes an immediate impression: That guy must be someone.

And he was. During the 1980s and ’90s, Richards was one of fashion’s most in-demand models. He traveled the world, appearing in campaigns for Versace, Valentino, Ralph Lauren and Cartier and was a favorite subject for photographers like Bruce Weber, Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton. In 1992, the Italian men’s magazine Mondo Uomo gave him a 58-page spread, while Vogue named him one of the top 25 male models of all time. He worked and socialized with the era’s A-list models, including Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington and Naomi Campbell, and has a ribald story about being sandwiched between the latter two—they were nearly naked; Richards was sporting a bustier—at a birthday party for photographer Steven Meisel. He was, no doubt, the first male supermodel.

As successful as Richards was professionally, however, he harbored a harrowing secret. For years, he was enmeshed within a shadowy religious sect called Eternal Values, which kept him psychologically enslaved with convoluted forms of love and abuse, reassurance and disapproval.

Eventually he would save himself, but he would never be the same.

At the end of the summer between his junior and senior years at Princeton, Hoyt Richards was discovered by a modeling agent and cast in an ad campaign for Jeffrey Banks. He was John Richards Hoyt back then—the professional name change would happen later. “The pictures came out that fall and all of a sudden I was one of the ‘new faces,’ ” he says now. “The agency was calling. They were like, ‘We’ve got a job for you in Tokyo on Tuesday.’ And I was like, ‘Listen, sorry, I’ve got a test.’ ”

It was an intoxicating experience for an All-American kid who just months before counted Friday night football games as among the more exciting events in his life.

Richards was the fourth of six children, born in 1962 in Syracuse, New York. His father was a Lehigh University–trained engineer and his mom, Terry, a Mount Holyoke alumna. Both families claimed roots in the American Revolution. When Richards was two, the family moved to a wealthy enclave on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Later on, at Princeton, he majored in economics and played varsity football.

Richards’ mother, however, had a difficult upbringing that Richards says likely influenced how she related to her own children. When her mother, an alcoholic, died at an early age, Terry Richards had assumed full care for her younger siblings. “When you come from that background,” Richards says, “you try to control everything because you don’t want to ever get hurt again. You develop this kind of bubble that you live in where it’s never your fault, and if anything goes wrong, you’re the victim.” As a child and teen, he tried very hard to please her. “[My mother] was very clear about what she expected me to be,” he says. “In order to get the love I wanted from her, I felt I had to try to become the thing she wanted me to be, even though that didn’t feel necessarily like who I really was.”

A gifted athlete from an early age, Richards gravitated to sports. “I was always drawn toward things that would have a crowd; with sports, you had that stadium,” he says. “All those eyes on me felt like maybe it would heal something. It’s the same reason I think I ended up modeling.”

Like many affluent families, the Hoyts summered in Nantucket, in an area called Shimmo and in a house his mom named Shimmo the Merrier. One day during the summer before his junior year of high school, Richards was at Nobadeer Beach—a kids’ hangout referred to by locals as “No Brassiere Beach”—when he encountered an older but still youthful-looking man drawing a yin and yang diagram in the sand.

Frederick von Mierers was full of ideas. Tall, gaunt and handsome, he spoke about Eastern philosophy, Hinduism and reincarnation. The attention he paid to the young Richards was invigorating. At the time, Richards was being forced by his parents to transfer out of his public school to attend the prestigious Haverford School, and he was not, he says now, in a particularly good place. “I was 16, he was in his thirties,” Richards says. “When you’re that age, having an adult who will talk to you like an adult gets your attention.”

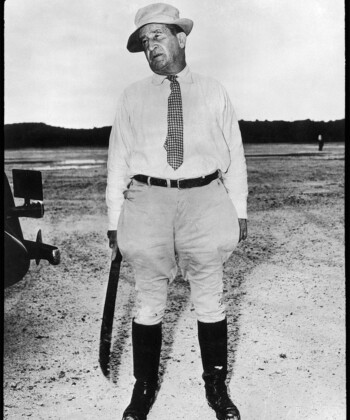

Frederick von Mierers, right, with a friend in the mid-1980’s

Von Mierers invited a bunch of the underage kids from the beach back to his place for beer. “I remember arriving there and knowing very quickly that this was clearly the cheapest beer you could buy,” Richards says. “I was not very impressed.” But the next summer von Mierers was back, and again the summer after that, and Richards continued to be drawn to him for reasons he can’t really explain. Freddy, as he came to be called, did Richards’ astrological chart and Richards, in turn, began reading Hindu texts and other books von Mierers suggested. He went from unimpressed to infatuated. “One year I was going to England. He told me the experience would really change my life—which it absolutely did, but it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure that out,” Richards says today. “I remember thinking, when stuff was happening to me, Freddy really is clairvoyant!”

NEXT: “We all had the feeling that we were on this critical mission that would help save ourselves, friends and family from the coming apocalypse.”