When Prenups Attack

by Natasha Wolff | October 6, 2016 1:30 pm

Just how fraught is the whole issue of prenups? Ask George Darren (not his real name) a prominent L.A. media executive. Darren loves his second wife very, very much. Only she is not his wife, despite the lavish Beverly Hills wedding. Virtually no one knows the truth—not friends, family, coworkers or children. The only people who know are their attorney and the one close friend who faux-married them. And why?

“My first marriage lasted four years and did not involve children, yet I lost one-third of all I worked for my entire life,” says Darren, 57, who came from a working-class family. “And I mean everything—a third of my house that she’d always signed quit-claims on, half of my retirement account. She even went after my frequent-flier miles. If she had taken the amount I wanted to settle for, she would have gotten the same as what she eventually did. But instead, she insisted I was hiding money, so hundreds of thousands went to attorneys and forensic accountants.”

Darren’s new wife, who has three children and a prestigious academic career that nevertheless pays a fraction of what he earns, also had a terrible divorce[1]: She had to pay alimony to her deadbeat ex. Yet she felt hurt by Darren’s insistence on the prenup. Life is too full of unknowns, she feels, to draw up a hard-and-fast contract like this. She’d rather rely on love and good faith. And so it stands, four years after their beautiful ceremony, that they are still not legally bound.

Given the current state of marriage, with divorce rates high as ever, it’s hard not to have sympathy for both points of view. He didn’t feel safe without a prenup; she didn’t feel safe with one.

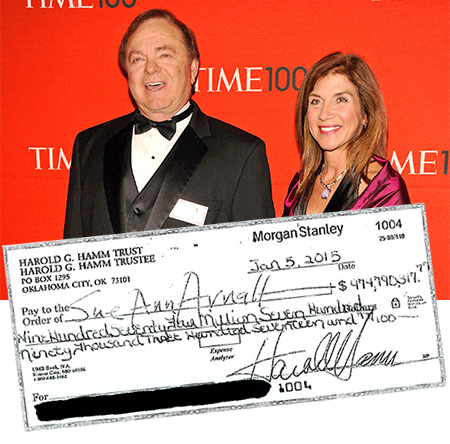

Prenups (and their malcontents) have been much in the news lately. There’s the story of Ken and Anne Dias Griffin, the wealthiest couple in Illinois. After Griffin, the CEO of Citadel hedge fund, who is worth an estimated $5.5 billion, blindsided his wife of 11 years with a request for a divorce, Dias Griffin—herself a wealthy and accomplished businesswoman currently worth about $50 million—has been trying to get her prenuptial agreement dissolved. Perhaps she is looking for inspiration in Sue Ann Arnall, ex-wife of Harold Hamm, the CEO of Continental Resources in Oklahoma. In January, with much media fanfare, Arnall rejected her ex-husband’s handwritten check for $975 million, saying it was far below what she, as a wife without a prenup, was owed after 26 years of marriage. (She relented after several days, but will still appeal the divorce case.)

Harold Hamm, possessing an estimated $10 billion oil fortune, wrote a check of almost $1 billion to Sue Ann Arnall, his prenup-free wife of 26 years. At first she rejected it.

These headline-making stories highlight an issue that’s of some concern even to those who are not in the one percent of the one percent: When can prenups, seemingly ironclad legal documents, be broken? Right now, only about three percent of all Americans have such agreements, but the overall number increased by 73 percent between 2006 and 2011, according to the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. And it’s not just the uber-wealthy who are getting them. Notes Byron Divins of Divins and Divins, P.C., whose Long Island practice does not have a particularly wealthy clientele, “A prenup can be just as bitterly disputed if the assets are not millions but maybe a few hundred thousand and the dog.”

“The problem with prenups as I see them is you can’t anticipate everything,” says Ellie Wertheim, a New York attorney whose distaste for the acrimony of divorce[2] led her to give up litigating and specialize in mediation. “So, what happens if you waive spousal support and then get sick or have a profoundly disabled child or need to care for a parent? Or you lose a job? The divorce actually happens, but the parties’ lives have deviated.”

NEXT: The 4 circumstances in which your prenup may be challengeable

It is still rare for a prenuptial agreement to be overturned. Yet these agreements are dissolved—sometimes. Think your prenup is challengeable? Here are the circumstances where you may be allowed to revisit history:

You (or your mate) didn’t live up to your part of a very specific bargain

In other words, you established a set of “musts” in the original document, and someone—maybe both of you—didn’t abide by them. For example, your wife promised to have children and didn’t, or she promised to have a certain number of children. (This was a stipulation in the prenup of a friend marrying an older, enormously wealthy man who already had six kids, but apparently had some sort of King of Siam fantasy. A certain payout would only kick in after the second. She delivered, just when she thought her eggs had given up the ghost.)

A recent inclusion? The social-media clause. Enough young couples have seen embarrassing or hostile postings on Instagram or Facebook wreck a romance, so now they are getting prohibitions or limitations on postings written into their agreements. (Surely this clause will be a source of litigation. The temptation to ignore it in a hotheaded moment is too great.)

You were tricked

What exactly constitutes fraud in the prenuptial contract? Lying about your finances for starters, says Connecticut attorney Gaetano Ferro, past president of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. In other words: Your mate said he was worth $1 million at signing, and he was worth $10 million. Whoops!

Of course, because many people are trying to negotiate their conjugal finances while maintaining the illusion of being swept along on gossamer wings, partners often waive their rights to this disclosure. In which case: Enjoy your prenup, because you’re probably stuck with it.

Yet another variation of fraud: when it is impossible for one party to understand what he/she is signing. “I had a case recently where the wife only spoke Russian and the agreement was in English,” says attorney Byron Divins. “Nobody used the expression ‘mail-order bride’ but basically that’s what she was.” It was not that difficult to nullify the prenup, Divins adds—though when it was over, Divins, who has lost only four trials in 18 years of practice, was more relieved than triumphant. “She was my client, but by the time it was all over I wanted to divorce her.”

You were strong-armed

Every week, says matrimonial attorney Raoul Felder, clients walk into his office and claim “duress” as their reason for breaking a prenup. The argument goes like this: At the last minute he was waving legal papers in my face. The wedding was planned, everyone booked their tickets and sent presents, so I would have signed a paper saying I was a space alien.

“That’s not duress,” Felder explains. “Even if it’s down to the wire and they’ve cued up ‘Here Comes the Bride,’ you have a choice about whether to get married or not.”

A prenup, in fact, halted the 2008 Palm Beach wedding of Wall Street trader Jason Bailer and Alexandra Fisher, an attorney and daughter of billionaire real estate magnate Jeff Fisher. “It was probably the most beautiful wedding[3] I’d ever been to,” says one attendee. “The chuppah alone must have been covered with 100,000 flowers.” But there was trouble in the flower-strewn paradise. According to press reports, the prenuptial had been signed but the bride’s father made additional demands on the wedding day, including the stipulation that in case of divorce the groom would still have to pay alimony to the bride. Discussing the terms of the future divorce on the wedding day perhaps did not set the right tone. But the attendee, who was close friends with the bride’s family, says the press got it wrong. “The groom”—who had his own money, but not Fisher-level money—“was demanding that he be paid alimony for life if the marriage ended,” she says. Whatever the true story, the million-dollar wedding was called off, but the party at the Breakers continued, with the now-non-groom’s family glumly drinking in one room, and the non-bride’s family in the other. After many tears, the bride eventually emerged—shaky and dressed in black. But she danced with her family. “She is not only beautiful and smart, but she was very close to her family, and she really understood that she was being protected,” the friend says.

Fisher has since gone on to a happy marriage. “In the end, everything worked out perfectly,” the friend adds. But perhaps it’s no coincidence that during the years she practiced family law in New York City her specialty included premarital and postnuptial agreements.

In order for “duress” to have any legal standing, Raoul Felder explains, there has to be the threat of real violence—pretty much a literal, not figurative, gun to your head. This was part of Anne Dias Griffin’s argument for scotching her prenup. Days before her 2003 wedding to Ken Griffin at Versailles (guest appearances by Donna Summer and Cirque du Soleil!), Dias Griffin had not signed their agreement, and her fiancé allegedly intimidated her by destroying a piece of furniture. (Griffin’s version, according to “Page Six”: He was gripping one pole of their four-poster bed, it broke and the bed collapsed.) There was also the emotional threat. Dias Griffin claims that two days before the ceremony she was bullied into visiting a therapist to settle their dispute—a therapist Griffin had an undisclosed business relationship with. He contends that before the visit, his future bride (who was formerly head of a hedge fund herself) had several lawyers amend the prenup, making it harder to argue that it was sprung upon her.

In December, a judge struck down Dias Griffin’s claims of emotional duress, leaving her with one further prenup-dissolving argument….

You discover… This sucks

The legal word is “unconscionable,” meaning that the terms of a contract are so grossly unfair or one-sided that no court could uphold it. Apparently in the prenup she signed, Dias Griffin was entitled to only one percent of her husband’s fortune. That doesn’t sound so great, until you realize that one percent of $5 billion for an 11-year marriage is not scratch. More importantly, the Griffins had some sort of complicated arrangement whereby millions of dollars of payouts have been made already, which further muddied the waters for her claim that the prenup was forced upon her and wildly unfair. Incidentally, none of this includes any child support for their three offspring, who presumably will not lack for future aircraft of their own.

Indeed there is recent precedent for a prenup being thrown out for being both signed under duress and unconscionable. Felder calls it “extremely rare,” but in 2013 Elizabeth Petrakis, wife of Long Island millionaire Peter Petrakis, worth at least $20 million, had her prenup dissolved when a court agreed that the document she signed four days before the wedding was “fraudulently induced.” In it, she signed away the rights to all marital assets, excepting $25,000 for each year they were married. The husband gave her a verbal promise that he would rip up the document when they had children. He didn’t.

Elizabeth Petrakis has since started a company called Divorce Prep Experts.

“Here’s the thing about shredding a prenup,” says Divins. “No matter what happens, no matter who gets what, very few people walk away happy.”

- divorce: http://dujour.com/lifestyle/divorce-separation-anxiety/

- acrimony of divorce: http://dujour.com/news/celebrity-divorce-attorney-laura-wasser/

- beautiful wedding: http://dujour.com/lifestyle/harriette-rose-katz-wedding-planner-stories/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/news/prenutial-agreement-loopholes/