A Shocking Life Story

by Natasha Wolff | September 27, 2016 3:00 pm

Heads turn as Hoyt Richards saunters through the low light and fashionable din inside the Petty Cash Taqueria, in Los Angeles’ Fairfax District. Six-foot-one with a chiseled jaw and a dimple, a forelock of gray-blonde hair cascading rakishly over one brow, he makes an immediate impression: That guy must be someone.

And he was. During the 1980s and ’90s, Richards was one of fashion’s most in-demand models. He traveled the world, appearing in campaigns for Versace, Valentino, Ralph Lauren and Cartier and was a favorite subject for photographers like Bruce Weber[1], Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton. In 1992, the Italian men’s magazine Mondo Uomo gave him a 58-page spread, while Vogue named him one of the top 25 male models of all time. He worked and socialized with the era’s A-list models, including Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington[2] and Naomi Campbell, and has a ribald story about being sandwiched between the latter two—they were nearly naked; Richards was sporting a bustier—at a birthday party for photographer Steven Meisel. He was, no doubt, the first male supermodel.

As successful as Richards was professionally, however, he harbored a harrowing secret. For years, he was enmeshed within a shadowy religious sect called Eternal Values, which kept him psychologically enslaved with convoluted forms of love and abuse, reassurance and disapproval.

Eventually he would save himself, but he would never be the same.

At the end of the summer between his junior and senior years at Princeton, Hoyt Richards was discovered by a modeling agent and cast in an ad campaign for Jeffrey Banks. He was John Richards Hoyt back then—the professional name change would happen later. “The pictures came out that fall and all of a sudden I was one of the ‘new faces,’ ” he says now. “The agency was calling. They were like, ‘We’ve got a job for you in Tokyo on Tuesday.’ And I was like, ‘Listen, sorry, I’ve got a test.’ ”

It was an intoxicating experience for an All-American kid who just months before counted Friday night football games as among the more exciting events in his life.

Richards was the fourth of six children, born in 1962 in Syracuse, New York. His father was a Lehigh University–trained engineer and his mom, Terry, a Mount Holyoke alumna. Both families claimed roots in the American Revolution. When Richards was two, the family moved to a wealthy enclave on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Later on, at Princeton, he majored in economics and played varsity football.

Richards’ mother, however, had a difficult upbringing that Richards says likely influenced how she related to her own children. When her mother, an alcoholic, died at an early age, Terry Richards had assumed full care for her younger siblings. “When you come from that background,” Richards says, “you try to control everything because you don’t want to ever get hurt again. You develop this kind of bubble that you live in where it’s never your fault, and if anything goes wrong, you’re the victim.” As a child and teen, he tried very hard to please her. “[My mother] was very clear about what she expected me to be,” he says. “In order to get the love I wanted from her, I felt I had to try to become the thing she wanted me to be, even though that didn’t feel necessarily like who I really was.”

A gifted athlete from an early age, Richards gravitated to sports. “I was always drawn toward things that would have a crowd; with sports, you had that stadium,” he says. “All those eyes on me felt like maybe it would heal something. It’s the same reason I think I ended up modeling.”

Like many affluent families, the Hoyts summered in Nantucket, in an area called Shimmo and in a house his mom named Shimmo the Merrier. One day during the summer before his junior year of high school, Richards was at Nobadeer Beach—a kids’ hangout referred to by locals as “No Brassiere Beach”—when he encountered an older but still youthful-looking man drawing a yin and yang diagram in the sand.

Frederick von Mierers was full of ideas. Tall, gaunt and handsome, he spoke about Eastern philosophy, Hinduism and reincarnation. The attention he paid to the young Richards was invigorating. At the time, Richards was being forced by his parents to transfer out of his public school to attend the prestigious Haverford School, and he was not, he says now, in a particularly good place. “I was 16, he was in his thirties,” Richards says. “When you’re that age, having an adult who will talk to you like an adult gets your attention.”

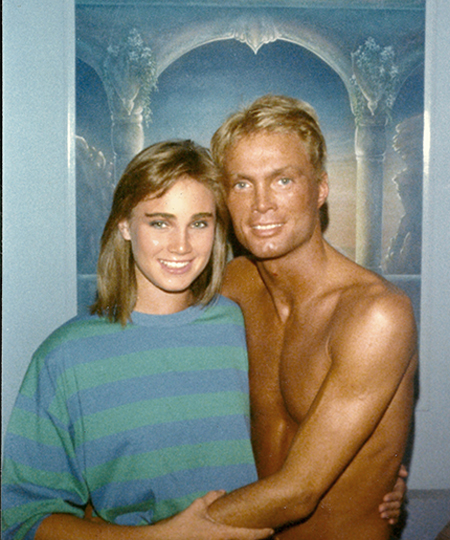

Frederick von Mierers, right, with a friend in the mid-1980’s

Von Mierers invited a bunch of the underage kids from the beach back to his place for beer. “I remember arriving there and knowing very quickly that this was clearly the cheapest beer you could buy,” Richards says. “I was not very impressed.” But the next summer von Mierers was back, and again the summer after that, and Richards continued to be drawn to him for reasons he can’t really explain. Freddy, as he came to be called, did Richards’ astrological chart and Richards, in turn, began reading Hindu texts and other books von Mierers suggested. He went from unimpressed to infatuated. “One year I was going to England. He told me the experience would really change my life—which it absolutely did, but it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure that out,” Richards says today. “I remember thinking, when stuff was happening to me, Freddy really is clairvoyant!”

NEXT: “We all had the feeling that we were on this critical mission that would help save ourselves, friends and family from the coming apocalypse.”

While he was at Princeton, and in the early days of his modeling career, Richards began visiting Freddy in Manhattan on the weekends. He and other young acolytes would go with Freddy to Studio 54, where it was impossible to get in without connections. Once inside, the group would see clubbers having sex on the dance floor and doing cocaine in the bathrooms, but Richards and his coterie had nobler pursuits. Freddy was against drinking and drugs. He thought the body was God’s temple. In the wee hours, the group would return to Freddy’s ornately decorated apartment to discuss Eastern philosophy.

“In my mind I was thinking that I was working him,” Richards says. “I was bringing up a couple friends with me from school, and we knew he could get us into Studio 54 and we could crash at his apartment. I was looking at it like I was taking advantage of this guy!”

By his senior year in college, Richards had signed with Ford Models and proudly paid for his last two semesters of college tuition himself. He graduated in the spring of 1985 and moved into an apartment in the same Manhattan building as Freddy’s. But there was much more to it than being neighbors. Richards was becoming part of Eternal Values, a cult led by von Mierers that counted a number of the building’s residents among its ranks. Starting then and for years after, Richards donated almost all of his earnings to the group, helping to cover the rent on the apartments Freddy kept in the building, as well as others he began to acquire as the group grew in number. When he wasn’t jetting off to a modeling or commercial job, Richards spent his days and nights doing menial tasks around the building or studying alongside Freddy and, despite his financial importance to the group, sleeping on a mat on the floor.

Eternal Values was founded in the early 1980s by von Mierers, himself a former model, interior decorator and socialite. An astrologer and self-styled prophet, he claimed to be an alien reincarnated from the distant star Arcturus. He said he had come to Earth to warn people of an impending apocalypse to be triggered by a change in the planet’s magnetic poles, and to train his students to become leaders in the aftermath.

Based out of von Mierers’ apartment building on the east side of Manhattan—the group also kept a loft in the Bronx and, later, a large house in North Carolina—Eternal Values attracted young, intelligent and often wealthy followers. Most were seeking a greater understanding of the universe; some were rewarded with a life of mind control and fanaticism. At its peak, there were perhaps 100 active members. They spoke in New Age jargon, with much talk about “highly evolved personalities,” “ego renunciation,” “the white light and the violet light” and the coming apocalypse, which made personal wealth and relationships unnecessary. Astrological charts and life readings, performed by von Mierers or one of his acolytes, played a central role. Included was often a “gem prescription,” adopted from Hindu belief in the healing properties of certain precious stones. “The gems are God’s thoughts condensed,” he told Vanity Fair in a 1990 interview.

Von Mierers’ East 54th street apartment in Manhattan

Von Mierers told followers he had connections for great deals on stones, which he often sold to them for more than $100,000; payments were only accepted in cash or traveler’s checks. “The gems were supposed to be the most pure forms of matter on our planet,” says Richards, who bought a fortune’s worth over the years. “They were supposed to strengthen your inherent weakness and enhance your strengths.”

Within the group, the number of gems one possessed was treated as a sign of devoutness. “I spent over $150,000,” Richards says. “The gems all came with bogus appraisals. When I sold them later, I found out they were worth less than $8,000.”

When Freddy’s story was included in a popular 1985 book, Aliens Among Us—“Dazzling true testimony that extraterrestrials are on earth,” the book promised—Eternal Values became a national phenomenon. Thousands of hopefuls contacted Freddy for astrological readings at $350 per session. Hundreds were drawn into his gemstone scams. Richards, then in his modeling heyday, was trotted out for interviews and appearances.

But while von Mierers was getting rich, Richards found in Eternal Values something more grounding. “The economy was kicking ass, there was opulence everywhere: a lot of drugs, a lot of cocaine,” says Richards. “Being in [Eternal Values], you had this sense that there was an alternative to all that. The message was, don’t be attached to this wealth and decadence because there’s really a higher meaning to it all. Freddy was basically saying, ‘Get your head out of your ass because the world is coming to an end—you better get your shit together because you’ve spent lifetimes preparing for this opportunity.’ ”

Gilberto Picinich joined the group in 1981 after hearing Freddy speak on the radio. A lifelong seeker, Picinich remembers the sense of purpose Eternal Values gave him. “We all had the feeling that we were on this critical mission that would help save ourselves, friends and family from the coming apocalypse,” he says. “The message self-validated over the years. You started to fear that if you left, you might miss something important, something that you’ve sacrificed for.”

NEXT: “It was like, ‘Let’s go to Madonna’s for the weekend!’ But I was like, ‘I can’t. The end of the world is coming.'”

Because Richards was the group’s golden goose, some felt he was given special privileges, “like flying around the world fucking beautiful models,” says Picinich. Yet while they lived off his money, the group felt that Richards’ work was inherently evil. “The fact that the world puts so much importance on someone who won a genetic lottery—to the point of putting a billboard in Times Square and paying that person hundreds of thousands of dollars—is the exact reason why the world needs to be destroyed,” Richards says in an attempt to explain the cult’s point of view.

He tried to downplay his secret life with the people he met as a model while making choices those colleagues didn’t understand. “Everyone else was living it up. It was like, ‘Hey, let’s go to Madonna’s for the weekend!’ ” Richards has said. “But I was like, ‘No, no. I can’t. The end of the world is coming.’ ”

As it was with his mother, it was with the cult. Nothing he did was good enough, but Richards kept trying. “More than anything, I felt like I’d made a commitment and I couldn’t give up,” he says. “Freddy had told us that we were responsible for our own lives—which I could deal with—but we were also responsible for the millions of people we were supposed to help, and that was a heavy trip that I couldn’t screw up.”

The hold Eternal Values had on him became so strong that he stayed on even after von Mierers’ death in 1990 from AIDS-related causes. According to Richards, the Manhattan district attorney’s office was investigating von Mierers’ gemstone scams at the time of his death, but discontinued after he died, when it was discovered that the self-proclaimed alien’s real name was Freddie Miers. He’d been raised Jewish in Brooklyn.

After Freddy died, there was a power struggle within Eternal Values. Freddy’s successors were even more extreme. As the years passed and the group relocated to a big house on Lake Lure, North Carolina, Richards continued to earn money and fame but the group became increasingly hateful toward him. He was often interrogated for hours on end about what they called his “ego lapses.”

“He was a good guy and a bit of a people pleaser,” Picinich recalls. “After Freddy’s death, the [new] leader was pretty cruel to him. You could see the toll it took.” Richards recalls some truly terrible behavior: “They said I was resistant and resentful of my chores, and that I was guilty of vanity and looking in the mirror—for that offense they shaved my head,” he says. “Mostly I would do menial jobs like scrubbing toilets and vacuuming. Any job they could think of that was a pain in the ass, they’d get me to do it.”

The abuse was also emotional. “My nickname was Dipshit. When I wasn’t in trouble, they’d call me Dippy, but generally I was just called Dipshit,” Richards says. “And this was after I’d been financing this thing for 15 years. Sometimes I would have to go out to the end of the dock and do belly flops as a form of self-punishment.”

Finally, on the night of July 3, 1999—after two previous unsuccessful attempts to leave the cult—Richards escaped, having tithed to Eternal Values the majority of his earnings, estimated at nearly $4.5 million dollars over almost two decades of work. He hadn’t spoken to his parents in 12 years. He turned to an old friend from his modeling days: Fabio Lanzoni, the long-haired and pectorally gifted spokesmodel best known for gracing the covers of hundreds of romance novels.

“When the shit hit the fan, he knew I would help,” Lanzoni says. “The other models used to make fun of him because he believed in aliens, but I’d tell them, ‘Listen, you shouldn’t make fun of him because there was something that happened in his life that put him in this situation.’ ” Richards lived in Lanzoni’s house in Los Angeles—and drove one of his Porches—for nearly a year.

On a recent afternoon, Richards sits on the sofa in his West Los Angeles apartment. He’s in bare feet and shorts; his forelock looks a bit limp. He recently wrote, produced and starred in a movie called Dumbbells, playing a guy who escapes from a cult and opens a gym. Another movie, Invisible Prisons, is in the works.

After he left Eternal Values, Richards says, he began doing a lot of reflection. As unbelievable as it sounds, never once during his two decades with the group did he ever consider he might be a member of a cult. In his mind, he was in a special group on an important mission; he believed he was one of the Chosen who would lead the earth into a new era of peace and prosperity. Like anyone suffering from Stockholm syndrome, he had no ability to objectify his experience. The reason he finally left the group, he says, was because he felt like a failure, unable to conform to their standards.

“And then one day I was doing some research, and it hit me,” Richards says, unabashed. “I was like, Oh, my God! I’m a textbook cult victim.”

In recent years, Richards has sought counseling and worked to build a film career. A civil lawsuit recouped some of his funds and effectively killed the remnants of Eternal Values. These days Richards feels that he’s finally reached a place of peace within himself. “I’ve come to understand that all this didn’t happen because there was something wrong with me,” he says. “It wasn’t because my mother didn’t love me enough. I was able to forgive myself. It’s how I was able to relieve myself of all that shame.” His great hope is that his story will be useful to others, “to make it cool for others to talk about their abusive situations, their fuck-ups.”

Likewise, he tries to make the best of his years with Eternal Values. “When you meet new people, you’re never quite sure when to mention it,” Richards says. “But I know one thing for sure: If I do bring it up, nobody ever finds my story boring.”

Shirt (worn throughout), $195, THEORY, bloomingdales.com[3].

Stylist: Sarah Schussheim. Groomer: Barbara Lamelza using Kevin Murphy hair products. Stylist assistant: Ashley Wong.

- Bruce Weber: http://dujour.com/lifestyle/bruce-weber-dogs-pictures-shinola-pet-accessories/

- Christy Turlington: http://dujour.com/news/christy-turlington-a-model-mom/

- bloomingdales.com: http://www.bloomingdales.com

Source URL: https://dujour.com/news/hoyt-richards-model-cult/