A Murder in Palm Springs

by Natasha Wolff | November 13, 2015 11:00 am

When Sophia Friendly opened the door to her killer, she was dressed for dinner.

It was October 12, 1978. In Palm Springs, California[1], a resort-home destination for presidents and entertainers—where Elvis and Priscilla honeymooned, where everyone from Frank Sinatra to Liberace held court—dressing for dinner was the protocol observed in many of the houses nestled in the desert valley. Sophia, age 71, donned a floor-length dress and gold shoes. Her husband, Ed Friendly, 74, put on a jacket. The couple’s maid set the dining-room table with crystal and a six-piece silver service that included slender fish knives.

At about 7 p.m. the killer walked in the front door of the three-bedroom Mediterranean-style villa at 893 Camino Del Sur. Something happened—words were spoken, a weapon revealed—and Sophia Friendly turned to flee down the hallway. She was shot in the back of the head and died instantly.

Frances Williams, the Friendlys’ 67-year-old cook and housekeeper, had just slipped a fish dinner into the warming oven. When the killer bore down on her in the kitchen, she dropped to her knees. A bullet to the head, fired point blank, ensured she died just as swiftly as her employer.

Ed Friendly wore a hearing aid. It is thought possible that, sitting in the bedroom, watching television and sipping a drink, he was unaware of the shots. He’d turned in his chair but had not risen to his feet when the killer struck a third time. Ed Friendly was shot twice—in the chest and in the head.

Photos and papers were tossed around, pants pockets turned inside out. Nothing was taken, including the $400 in cash in plain view in a wallet. But something was left behind: shell casings on the floor of the hallway, kitchen and den. Those casings would prove crucial but not for more than 30 years, after waves of police work drew tantalizingly close to an arrest time and again. The casings held the clues.

The killer did one thing more in the house on Camino Del Sur: A man’s fedora was tossed over the face of Sophia Friendly. It was as if to deliver the message that her death held the most meaning.

No neighbor observed anything out of the ordinary; no one heard gunshots. A car could have easily glided down the dim, quiet, palm-lined street unnoticed, the smell of dust and fig groves in the arid breeze.

It was the first triple homicide in the history of Palm Springs.

The next afternoon, Friday the 13th, Suzanne Friendly, a 36-year-old ABC network television producer in Houston, had just finished working on a commercial for Battle of the Network Stars when the phone rang in the editing room.

Suzanne remembers, “Both of the men that ran the company were there, and one man was going, Oh, no! He hung up and said to the other guy, who was the vice president, Do you want to take a walk with me?” Suzanne turned to her group of co-workers and said, “They probably have a problem with the promo for Battle of the Network Stars.”

The executives spoke in the hallway and then returned to the editing room. One of them, Jay Michaels, said to Suzanne, “We need to talk to you.”

She thought she’d made a mistake on the commercial reel, so she said, “Whatever it is, Jay, I can fix it.” Her boss guided her out of the room, touching her elbow, and cautioned, “I have some bad news for you. Your father.”

Ed Friendly had been scheduled for prostate surgery that day; his daughter, Suzanne, called him at home the previous night at 5 p.m. Houston time, to wish him luck, but no one answered the phone. “Oh my God, my father’s had a heart attack,” she said. And then, in a rush: “Oh please, don’t make me go down there. Let me do the show. My stepmother is—my stepmother is, you know, not a nice person. I just can’t be around her. She’ll be hysterical.”

“It’s your stepmother,” Suzanne’s employer said.

“My stepmother had a heart attack?” she responded.

“Well,” he said, and hesitated. “And the maid.”

“What are you telling me?” she asked, bewildered.

“They were all murdered.”

Suzanne Friendly remembers every word and gesture of how she was told of the deaths, but the rest of the day is a blur. She knows that she immediately flew to Los Angeles and was driven to Palm Springs, which is about 125 miles east. When she arrived, yellow crime-scene tape sealed the house. It wasn’t until the next day that she was permitted to enter and had the first of many conversations with police.

Suzanne learned that at 7:30 that Friday morning, the regular pool maintenance worker was beginning to clean the Friendlys’ pool when he noticed something eerily wrong through the window. What appeared to be a dead body lay in a pool of blood in the kitchen.

Ed and Suzanne Friendly

“It was a horrific murder scene,” says retired Palm Springs detective Tom Barton today, one of the scores of police who responded to the pool worker’s call. The Desert Sun reported that the three bodies were found in “grisly disarray” and that the warming oven containing their fish dinner was still on.

“I see them come and go, but everyone in this neighborhood pretty much keeps to themselves,” a neighbor was quoted. Others said they’d had cordial conversations with Ed Friendly about such problems as raccoons in the garbage. The Friendlys moved to Palm Springs in the early ’70s and bought the house in Vista Las Palmas in 1976.

Other than the shell casings ejected from the weapon, there was little if any physical evidence. Barton remembers that members of the local police department performed a three-block grid search looking for a weapon. Nothing.

It is axiomatic that the initial stage of a criminal investigation is crucial to solving a murder. The Riverside County District Attorney’s office took jurisdiction of the Friendly case. Police ruled out robbery as the motive. At first detectives focused on the background of Ed Friendly. His business ventures hadn’t always gone well. Ed came from a well-to-do family back East; his brother Alfred was the managing editor of The Washington Post. Ed was a realtor[2] and a stockbroker. In California he was an executive at various racetracks, including one that burned down after he negotiated its sale. Maybe someone from one of Ed’s failed deals had a motive to come after him.

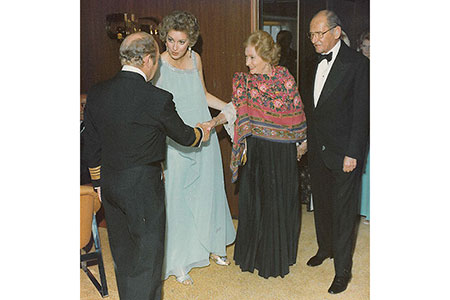

Sophia and Ed Friendly, on right, are greeted at a society function

But interviews with Suzanne Friendly led detectives to look more closely at her stepmother. Sophia Friendly, the former Sophia Brownell, belonged to San Francisco society and was on the city’s Social Register. Ed was her second husband. For 24 years she was married to Curtis Wood Hutton, a nephew of Edward and Franklyn Hutton—the founders of E.F. Hutton—and a first cousin to the famous Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, known in the press as the “poor little rich girl.” Sophia and Curtis had a son and daughter, Edward and Sophia, before divorcing. Police were very interested to learn there was bad blood between Sophia and her children. The acrimony was about money. There were accusations. A lawsuit. Estrangement.

Further investigation revealed the existence of inherited money. According to conversations with family members, Sophia Friendly was the beneficiary of multigenerational trust funds. Sophia’s ex-husband, Curtis Hutton, was the beneficiary of a $1 million trust fund awarded to him years earlier by Barbara Hutton, who considered him a favorite cousin. But there was a twist to the trust: If Curtis preceded her in death, Sophia would receive the money, not the children. Curtis’s son and daughter would inherit only if their mother died before their father.

NEXT: “Something upped the ante from grudges and tensions to a pistol fired…”[3]

There was more. Curtis Hutton, it seems, was terminally ill, so the matter of who died first was critically important to the inheritance. About three weeks prior to the murder of the Friendlys and their maid, the weakened Curtis had visitors in his home in Santa Barbara, California: his 39-year-old son, Edward, and a friend of Edward’s named Andreas Christensen. It was well known that Edward Hutton was under severe financial strain: stalled career, a bad divorce, mounting debts.

And while Edward visited with his father, he talked about guns.

Fortunes carved out long ago quite possibly set the stage for the tragedy on Camino Del Sur. They were quintessentially American fortunes, forged by people of determination, on the West Coast and the East. Many upper-crust descendants contend with divorce, neglect, infidelity and failure—even suicide. But hundreds of hours of interviews with members of the Hutton and Friendly families, with their friends and employees, and with police officers and forensics experts in three countries, reveal a lethal level of dysfunction. Something upped the ante from grudges and tensions to a pistol fired into the brains of three helpless old people.

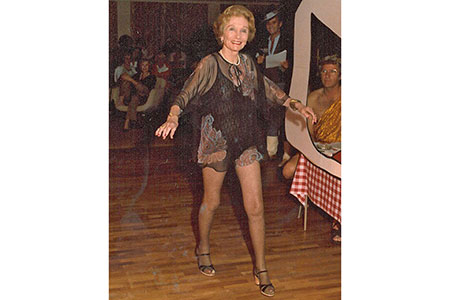

Sophia Friendly

Sophia Friendly, most likely the key to the triple murders, was the daughter of a respected San Francisco doctor, Edward Earle Brownell. Her inherited wealth came through her mother’s family, the Talbots.

Sophia was a descendant of Frederic Talbot, a true pioneer. On December 1, 1849, he arrived in San Francisco with his partner, Andrew Jackson Pope, by sea. They’d left their homes in East Machias, Maine, 51 days earlier, taking the harrowing route around Cape Horn. They were immune to gold fever, at its height, but alert to other opportunities created by vast natural resources and an influx of people. Talbot and Pope started a barge company and then moved into lumber. The partners purchased land in Oregon and built a mill on Puget Sound. Business exploded, with the lumber shipped to Japan, Australia, South America, China, Korea and Africa. By 1881, Pope and Talbot owned four sawmills, 19 ships and thousands of forested acres in the Pacific Northwest and Maine.

Sophia’s mother was a wealthy and socially prominent San Francisco matron who made sure her daughter had a brilliant society debut in 1924. A dainty and pretty copper-haired girl, Sophia wanted to be an actress and moved to New York City[4] in her early twenties. She didn’t find a theatrical career. But she did find Curtis Hutton, nephew of the founders of E.F. Hutton.

The Hutton siblings were Edward Francis (E.F.), Franklyn Laws and Grace. E.F. and Franklyn achieved a tremendous amount through sheer hard work on Wall Street. But they were also catapulted to the American stratosphere of East Coast society by marrying heiresses.

E.F. Hutton, who dropped out of school and worked in the mailroom of a securities firm at age 17, married Marjorie Merriweather Post. She was the only child of C.W. Post, the Midwesterner with chronic stomach problems who turned his idea for a cold breakfast cereal into the behemoth named General Foods. E.F. Hutton and Marjorie entertained widely and built some of the most spectacular houses in America, including Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, which was declared a National Landmark (Donald Trump bought it in 1985).

E.F. Hutton and his second wife, heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post

This would appear a hard marriage to top, but Franklyn Hutton seemed to have done that when he wed 20-year-old Edna Woolworth, one of three daughters of Frank Winfield Woolworth. F.W., as he was known, started out with $300 and two five-cent stores: one in Utica, New York, and the other in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. By 1911, the F.W. Woolworth Company had 596 stores; its owner had transformed American retail. Woolworth is credited with being the first to buy merchandise direct from the manufacturers and then set the prices himself; he also created self-service display cases so shoppers could look at goods without needing a salesperson. In 1913 he built the neo-Gothic Woolworth Building in Manhattan for $13.5 million—in cash—and it remained the tallest skyscraper in the world until 1930, when it was topped by the Chrysler Building.

When Franklyn met Edna, she was 17, shy and lovely. Their wedding was at the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest on Fifth Avenue and 90th Street. Edna and Franklyn Hutton later moved into a fifth-floor suite at the Plaza Hotel. Their only child, Barbara, was born on November 14, 1912. But the marriage foundered. Barbara wrote of her mother many years later: “Like several other frustrated wives of the Plaza, she became a sad regular at the hotel bar, draping herself over the railing and asking the bartender in too loud a voice to guess when her husband had last slept with her.” Amid rumors of Hutton’s adultery, Edna, 27, was found dead on the floor of her Plaza suite, wearing a white lace dress embroidered with gold irises and a double strand of pearls. Some say a maid found the body; others that it was 5-year-old Barbara.

The New York Times reported, “According to New York City Coroner David Feinberg, who later asserted that an autopsy was unnecessary, death was due to a chronic ear disease.” The truth, according to biographies of Barbara Hutton, was that Edna Woolworth Hutton took a fatal dose of strychnine and her father paid the coroner’s office to cover it up. When a reporter later asked to see the files of the case, the coroner’s office said they had been “misplaced.” Those files were never found.

But what to do with little Barbara Hutton? At first she was placed with her grandparents, who lived in a 62-room Italian Renaissance mansion in Glen Cove, Long Island, and employed an army of servants, including 70 full-time gardeners. But F.W. died, and his widow, Jennie, was in the throes of dementia. Barbara was shipped off to live with her aunt Grace Hutton Wood in Altadena, a suburb of Los Angeles. Barbara’s father later had them moved to a large estate in Burlingame, on the San Francisco peninsula. He saw little of her, although he carefully guarded and invested her fortune. By the time she turned 21, her father had reportedly increased her fortune to $24 million ($754 million in today’s dollars).

Barbara Hutton, the heiress to a fortune, watches a tennis match in Palm Beach, Florida. She married Cary Grant two years after this picture was taken.

Barbara Hutton would squander that fortune, marry seven times (including to Cary Grant) and struggle with both addiction and the strain of being followed everywhere by reporters. It is said that when she died she had just $3,500 left. Barbara was famously—almost pathologically—generous, showering acquaintances with gifts. There were few people she was close to, but one of them is said to have been her older cousin Curtis, son of Grace. He was kind to the withdrawn and lonely girl.

Curtis’s father, Benjamin Wood, did not stay married to Grace Hutton very long; years after the divorce, Curtis switched his middle and last names and became Curtis Wood Hutton. He was a sportsman, good at polo, and worked briefly as a stuntman in Hollywood. Later he moved to the East Coast, where he met Sophia Brownell.

After Curtis and Sophia were married, Barbara Hutton gave her cousin the $1 million trust. The trust income went to Curtis throughout his lifetime; when he died it would be liquidated and paid out to his children. Curtis bought a ranch near Santa Barbara and lived quietly with his family.

But in 1941, Curtis, then 41 years old, wanted to serve his country in World War II. Sophia would agree to his enlisting only if her husband signed an irrevocable agreement that, upon his death, the Barbara Hutton Trust income would go to her so she could support herself and their children. If she pre-deceased him, the original inheritance would stand and the children would inherit. Curtis agreed, and the clause was signed on January 9, 1942.

A portrait of Curtis Hutton in his World War II naval uniform

Despite Curtis’s coming back from the war alive, the agreement could not legally be changed. This might not have caused a problem except for the fact that in 1951, Curtis and Sophia Hutton divorced.

According to relatives, Sophia was a distant mother who relied on nannies to take care of the children. Nonetheless, after the divorce, the two youngsters moved with their mother to San Francisco, to live in a townhouse at 2507 Broadway purchased by Curtis. The townhouse was in the children’s names, but Sophia had the right to dwell there for the rest of her life. Also helping out the family was Sophia’s mother, who some believed had a reported $12 million inherited fortune. (In 1953, Sophia married Ed Friendly, himself divorced and the father of Suzanne and Tony.)

NEXT: “He was broke and owed money to everyone.”[5]

Sophia and Curtis’ son, Edward Hutton, attended prep schools, followed by Columbia University. Numerous interviews paint a portrait of a bear-sized man (six-foot-five and more than 250 pounds) with a taste for luxury. He married Columbia classmate Caroline DuBois in 1963.

But he could not hold a job. Despite being the grand-nephew of the Hutton brothers, he was hired and fired from 12 different brokerage firms between 1964 and 1977. In the early 1970s, Edward and his young family moved to London, where he continued to struggle financially. At the end of 1976, his marriage ended.

Edward Hutton in top hat, with his wife, Caroline, celebrate with friends

It has been widely reported that 1977 was a turning point in the tense and tangled lives of the Huttons, Friendlys and Brownells. Suzanne admits that her father was seen as the “scoundrel” of the extended Friendly family. This view was echoed by others. “The Friendlys ran out of money,” Sophia’s brother, William Brownell, later told the San Francisco Chronicle. “They were more or less living off my mother while she was alive.” The San Francisco townhouse did not belong to Sophia; it was in her children’s names. In the early ’70s, she arranged for the children to sign over rights to the property so that she could sell it. She then used the proceeds to put a down payment on her first house in Palm Springs. Edward and his sister, Sophia Merrill, complained and pressed for some share of the sale of the house. Their mother refused. Ed Friendly warned his stepchildren that if they continued to protest, they would be disinherited. Instead of backing off, the younger Sophia sued her mother. In 1977, Sophia Friendly had a codicil added to her will disinheriting her two children. “My sister’s relationship with her children was never satisfactory,” William Brownell said in the same newspaper story. “She wasn’t the motherly type at all. And she was extremely selfish.”

Edward Hutton, who has declined interview requests in the past, confirmed to DuJour that there was animosity. In one of two e-mails to this writer, Hutton said, “My relationship with my mother at the time of her death was somewhat strained because she and my stepfather swindled my sister and I out of the proceeds from the sale of our San Francisco home…We subsequently found out that she used that money to pay off [gambling] debts of our stepfather.”

Edward Hutton also confirms he met a man named Andreas Christensen in London in the 1970s. Although it is difficult to piece together Christensen’s background, Caroline Hutton, Edward’s ex-wife, now says, “Andreas had met Ed in one of the pubs of London. They became thick as thieves. Andreas always had stories of his adventures either in one business or another or his time working as a mercenary. He would also have a number of passports. He was dating a lovely woman named Katja Nielsen and, as I would later learn, he took her for quite a bit of money. Katja worked while neither Ed nor Andreas had a steady job. Every morning the two of them would walk her dogs for her while she was at work.” (Andreas Christensen did not respond to numerous attempts to interview him for this story.)

In 1978, Edward Hutton, heavily in debt, returned to the United States, leaving his children, Virginia and Teddy, behind in London with his ex-wife. Custody disputes raged. “He was broke and owed money to everyone,” Caroline said. Hutton ended up in Houston, vaguely connected to a new French restaurant called La Seule Etoile. In 1978, Texas Monthly magazine ran the following item:

“If you order quail or veal at Houston’s new Le Seule Etoile (the Lone Star) restaurant, chances are it will be prepared by E.F. Hutton. This is not the E.F. Hutton but the great-nephew of the millionaire stockbroker and a part-owner of the restaurant, which he opened in July after ‘travelling all over the world as a professional eater and drinker.’ On the way, he picked up a few trade secrets from European chefs. When E.F. Hutton cooks, people eat.”

The Hutton family in happier times. (From left) Teddy, Caroline, Virginia and Edward

In September of 1978, Andreas Christensen arrived in Houston. Two weeks later, the two men flew to Los Angeles, rented a Ford sedan and drove to Santa Barbara. Edward Hutton had gotten a call from his sister. Their father, Curtis Hutton, was dying.

In Palm Springs, in the weeks after the murders of Sophia and Ed Friendly and Frances Williams, the police detectives, learning of the various trust funds, were pushing forward on several fronts. Barton says, “We enlisted the help of one of the young detectives on the squad. He was a college grad and knew how to use computers. Within a day he had put together a six-foot-long flow chart of the Brownell and Hutton families and their family histories and trusts. We quickly dispatched detectives to San Francisco to interview members of the Brownell family and four detectives to Santa Barbara to interview Curtis Hutton and his daughter Sophia.” Edward Hutton was located in Houston, and Barton personally flew there to interview him.

Sophia Merrill says today: “I had called my brother Edward to let him know that our father was gravely ill and that I was helping … take care of him and I thought that he should come and visit. A week or so later he arrives in Santa Barbara with this strange man he had not mentioned before. His name was Andreas Christensen, and he was introduced to us as a good friend of Edward’s from his time in London. They had supposedly worked together, but at what was something of a mystery.”

Christensen made the family uneasy. He “was scary and cold as ice,” Sophia Merrill says. “The first day of their visit, Edward, with Christensen standing right there, asks my ill father if he can have his gun collection. Without saying it, he meant after my father dies. It was terrible. This did not please my father, and I thought it was insensitive and horrible. We had an uncomfortable fish dinner at the Biltmore, one of the more fashionable restaurants in Santa Barbara. During dinner I asked Christensen why he had dyed what looked like blond hair to a darker color. It was a steel color and looked all shiny. He gave me some excuse that he was going to a Halloween party or some such nonsense.”

(In the e-mail sent this year, Hutton says, “Andreas Christensen never communicated nor saw my father, never entered his home, nor did he or I ever discuss his gun collection.”)

To continue his murder investigation, Barton flew to Houston and was met by a young homicide detective of that city, Johnny Donovan. They headed for Le Seule Etoile, which actually belonged to a man named Henry Kelsey. Hutton had functioned as a sommelier for his friend. But Kelsey was disenchanted—later it was alleged that Hutton sold bottles of wine at inflated prices to customers and pocketed the money. (According to Hutton, “Mr. Kelsey and I had a difference on opinion on running a restaurant.”)

Kelsey told detectives that a month earlier Hutton had introduced him to Christensen in the restaurant. He was astounded when the Danish man asked him to purchase a gun. Kelsey emphasized to police, “Needless to say, I refused.”

Kelsey suggested that police interview the maître d’, David St. John, and the head waiter, Antonio Garrido. Barton remembers the 21-year-old St. John as a courteous and good-looking former college soccer player. “The kid was a bit hesitant,” he remembers. Still, they formed a bond. St. John “was talking to me about what it was like to be a detective, and he’s thinking that he might want to one day be an FBI agent or detective. I gave him my card and told him to call me if he wanted to talk about that or anything else. It turned out to be a good move.”

With St. John, the police struck pay dirt. The maître d’ said Hutton and Christensen told him they both belonged to a prestigious gun club in London and that Christensen wanted to purchase a .45-caliber handgun to add to his collection. The problem was that as a foreigner he could not legally purchase a weapon. Hutton explained that you needed a valid Texas driver’s license to purchase a gun but he had not been issued one yet. Garrido said they prevailed on him to buy the gun for them. Garrido went with Christensen to a pawnshop and confirmed that he bought one but was unsure of details.

Shortly after the triple homicide, detectives had put out a wanted-for-questioning alarm for Christensen, but he’d quietly left the country. The detectives contacted Interpol and put Christensen on their wanted list.

Edward Hutton, though, was interviewed twice by detectives in Houston. Hutton had proof that on September 25 he’d flown back to Texas and not left. He initially said he met Christensen at the Los Angeles International Airport when he was on his way to visit his father. “At first he also lied about taking Christensen to Santa Barbara to meet his father, but later admitted he did it,” Barton said. “The detective working with me quickly established that Hutton did indeed have a Texas driver’s license.”

Hutton agreed to a third interview with police, when he was supposed to voluntarily take a polygraph test. But Hutton did not show up at the appointed time.

NEXT: “Where is the justice?”[6]

Barton flew back to California. There the next breakthrough came: A woman forensics expert identified the murder weapon as a Spanish-made Star PD .45-caliber pistol. According to Barton’s former partner, detective Fred Donnell, “It surprised me that there was only one manufacturer at that time that manufactured the right-to-left or left-to-right twist. All the others were the other way, so that narrowed down to what brand or model the gun was.” (When a bullet is fired from a handgun it spins either right or left. The spin creates marks on the recovered bullet that establishes what spin is being used.) With the bullets and shell casings in hand, the expert was also able to establish that the bullets were .45-caliber hollow point CCI Speer ammunition.

On October 26, 1978, Curtis Hutton died in Santa Barbara at the age of 77. Within months, Edward Hutton and Sophia Merrill split the Barbara Hutton trust, which had grown to $1.3 million. They also inherited trust money from their mother’s side of the family that could not be altered by any will codicil. It was money from the same trust that was funded by the Pacific Northwest lumber empire of Frederic Talbot. A recent trust statement of Edward Hutton’s indicates that he still receives approximately $96,000 a year from his mother’s family’s trust.

Detective Barton also received an important phone call from David St. John, who admitted he had not been completely candid when they interviewed him in Houston. St. John now said he was absolutely sure the weapon that Garrido had purchased for Christensen was a .45-caliber handgun and the place he bought it was the Bellaire gun shop just outside of Houston.

The case was hurtling toward arrests, police believed. The Houston authorities spoke with the gun-shop owner and confirmed Garrido’s purchase. There was a receipt of sale. To complete the case in Palm Springs, the receipt would have to be obtained and the shop owner interviewed.

But in the first of several serious setbacks to the case, Barton’s superior officer said he had spent too much of the county’s money already and refused to allow him to return to Houston. He was told to ask one of his superior officer’s FBI golfing buddies to pick up the receipt. It took the FBI two months to get the document.

A couple of months later, there was another significant death.

A friend of Edward Hutton’s who lived on Manhattan’s Upper East Side named Enid Jones-McSherry remembers that in February 1979, she received a call from the Houston police asking to speak to Edward. He was indeed staying with Enid and her late husband, Jack, and she handed him the phone.

The police had news: David St. John had been found dead in the bathtub of Edward Hutton’s Houston apartment. When told the news over the phone, Hutton “did not seem concerned,” said Enid Jones McSherry.

(In the second e-mail to the author, Hutton says that when David St. John died, “I was in London with my children,” and St. John was staying in the Houston apartment “so it couldn’t be robbed.”)

Barton said, “Houston detective Johnny Donovan calls me all heartbroken and apologetic. St. John had been found dead in Hutton’s apartment over the weekend and the uniforms treated it as just an overdose. They had not checked about his being a potential witness in a murder investigation. It was hard to believe that this strong, healthy kid would die from a combination of booze and cocaine in Hutton’s apartment.”

Incredibly, Garrido, the headwaiter, died not long after St. John. The young man who told police he purchased a .45 pistol for Christensen was gunned down by a hitchhiker he picked up on a drive to Arkansas. The murderer was caught and given a 50-year sentence.

And so, a year after the murders of Ed and Sophia Friendly and Frances Williams, when the family and press were impatiently awaiting arrests, there were none. Riverside County prosecutors did not lodge charges. The key witnesses to the gun purchase were both dead. There was no murder weapon in the possession of the police. Christensen had disappeared.

But on June 19, 1981, Detective Fred Donnell received a phone call that changed everything. It was from Interpol. Danish police just arrested an Alfred Borg in a bank robbery. But that wasn’t the man’s real name. It was Andreas Christensen.

Denmark is ahead of the curve in environmental protection. In 1981 it was a violation to leave a car motor on and let it idle for more than five minutes. And so a passerby called police to report a car sitting outside a bank in a Copenhagen suburb with its motor on, a woman standing next to it. The responding officer caught Christensen as he emerged from the bank. He and the woman, a native of Zimbabwe, were charged with robbery.

Detectives Barton and Donnell flew to Copenhagen to interview Christensen. He spoke freely for two days, appearing very relaxed and sure of himself. “He mouthed off to me a few times as though he were a tough guy, but I would not let him get away with that,” Barton said. Amazingly, Christensen admitted to having the gun in Houston and to visiting Curtis Hutton in Santa Barbara with his friend Edward. He said he no longer had the gun because he broke it down and threw the pieces from a moving train in Austria. Christensen also admitted to being in Los Angeles two days before the murders, ostensibly for some import-export business. He said it was possible that he was in Palm Springs on October 12, 1978, and that he had gone there to see a young woman—the daughter of actor Robert Stack. (Stack and his daughter denied meeting Christensen.)

But as with the interviews of Hutton, cooperation abruptly stopped. The next time detectives tried to speak to Christensen, he refused. There was to be no jailhouse confession.

Independent investigation revealed hair-raising details about Christensen. He had spent the last few years in Zimbabwe as a mercenary. Barton flew back to the U.S., but Donnell pressed on to South Africa. According to reports in the San Francisco Chronicle, a former girlfriend led the police officer to a cave that Christensen used. There they found hand grenades, explosive mines, weapons and, most importantly, CCI Speer .45-caliber ammunition. The ex-girlfriend remembered Christensen writing letters to someone in Houston—she did not know the name—demanding payment of $150,000.

When detectives and prosecutors regrouped in Palm Springs, they decided to prosecute both Edward Hutton (remarried and still living in Texas) and Andreas Christensen. The Danish court went ahead and formally charged Christensen with the three murders in California. Christensen applied to become a Danish citizen again because the country would not allow the extradition of an accused person to a country that carried the death penalty.

But then there was a change of course. Despite nearly three years of work by the detectives as well as the help of the Danish, English and Zimbabwean authorities, the prosecutor’s office pulled the plug on the investigation. The suspected reason: money problems in Riverside County. Tiny Palm Springs is wealthy, but vast Riverside Country is not. The fourth most populous county in California, Riverside stretches from Orange County to the Arizona border. “It’s blue collar,” says a police officer. Budgets are strained. Sources say that the authorities feared a multiple-defendant first-degree murder trial involving extradition from a foreign country would bankrupt the county. In 1971 the Manson Family murder trial, which involved multiple homicides and multiple defendants, cost the state of California nearly $1 million. And it could not be denied that the Friendly murder case had weaknesses: no witnesses, no weapon, no confessions and circumstantial evidence.

Furious, the Danish dropped their murder charges and Andreas Christensen was prosecuted only for bank robbery. The Palm Springs case lay dormant. Murders do not have a statute of limitation and remain categorized as open. After serving several years, Christensen was released and lived in Denmark, keeping a low profile. Edward Hutton left the United States in the mid-1980s and took up residence in Brazil. If the Palm Springs case ever progressed to arrests, there needed to be two extraditions from foreign countries.

The inability to make arrests in the Palm Springs murders haunt the police who spent years investigating it, including Fred Donnell. “I was working Monday through Friday, and then on Saturday and Sunday I was still working on it. I’d bring stuff home,” says Donnell. “I’ll take it to my grave.”

In 1986, Hutton’s teenage son, Teddy, committed suicide. Hutton did not help pay for the funeral, says Caroline Hutton, who has waged legal battles seeking child support for years. In 2006, Edward Hutton, as part of the disputes, wrote a Connecticut judge a letter saying, “I am presently 67 years of age, retired and living in Mexico.” He is deeply estranged from Virginia, who sent him an anguished letter, “Do you recall the time that Teddy and I did not see you for four years? We called you and called you and said we wanted to see you; you made lame excuses… You know nothing about me. How tall am I now? Who are my friends?”

The Friendly family could not heal, either. Tony Friendly, the son of Ed Friendly, told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1995, “There’s not a day that I haven’t thought about this. My father and I were at odds when he died—we were on bad terms. So when he suddenly died it was an open-ended thing… I think that if he had lived, there would have been a reconciliation. We would have resolved our problems.”

The Palm Springs murders haunt not only family and police but also journalists. In 2006, former San Francisco Chronicle reporter Michael Taylor, who has written the most in-depth stories of the murders, contacted the newly elected district attorney of Riverside Country, Rod Pacheco. He suggested the DA’s office reopen the case. Pacheco, after getting up to speed, assigned it to assistant district attorney Bill Mitchell, considered one of the best homicide prosecutors in California. Mitchell says now, “Under California law, it is easy to file charges against someone in a case, but for old cases, unless the DA can produce new evidence that was not available years ago, the defense can have the case thrown out. We did not want that to happen here.”

Pacheco assigned the Friendly murders to veteran Riverside investigator Richard Twiss. Remarkably, Twiss was able to come up with a tantalizing potential new source of evidence linking the murderer to the 1978 crimes. Dr. John W. Bond, a British chemistry professor, created a procedure for lifting prints off metal objects. “When someone loads bullets into a gun, very often the sweat on the fingers is transferred to the bullet,” explains Dr. Bond. “When the gun is fired, the heat from the explosion etches the print like a tattoo on the shell casing.”

Hoping that the shell casings found on the floor of the Palm Springs house could undergo these tests, police sent them to Dr. Bond. Success. “I was able to lift a number of good prints,” he confirms, “but they are believed to be primarily the sides of someone’s fingertips,” an area not usually captured. Authorities have Christensen’s prints, but they need to do a new and thorough, side-to-side inking to determine a match.

A critical piece of evidence on who murdered Sophia and Ed Friendly and Frances Williams—the sort of evidence that brings indictments—was literally at hand. Authorities had information that Christensen lived outside Copenhagen under an alias. Informal efforts were made to try to acquire new prints, but no formal request was ever made by the Riverside County authorities to the Danish government.

In 2010, Pacheco lost the election to become district attorney and the new DA, Paul Zellerbach, reportedly fired Mitchell and took Twiss off the case. Momentum has been lost again. Zellerbach’s spokesperson, John Hall, refuses to say whether the county’s fiscal problems were the reason for nothing being accomplished. In the latest phone call, Hall said, “At this time the case remains open. There is not enough evidence at this point to file any criminal charges. As with any open case, should further information or evidence develop, we would then review that evidence for a possible criminal filing decision.”

In the years since her boss led her out into a hallway to tell her that her father was murdered, Suzanne Friendly has had a full and successful career in television. She retired from Warner Brothers Television a decade ago and works part time. But she is still troubled by the lack of answers. “I cannot believe that after all these years the two men suspected of murdering my father and stepmother have never been brought into a court to face the charges,” she says. “Where is the justice?”

Caroline Hutton, who now lives in Connecticut, wrote a letter to California Governor Jerry Brown in the spring of this year: “Sophia Friendly was my mother-in-law, and I represent her granddaughter, Virginia Hutton, who wrote several letters in February to various agencies but has received no replies. I think the family deserves an explanation for why this case has been dropped—if it has. And if it has not, where it stands now.” California’s deputy attorney general, Sabrina Y. Lanerwin, replied in a letter that “California law gives discretionary authority to a locally elected prosecutor in filing criminal charges. The decision … calls for consideration of the prospects of obtaining a conviction against a particular defendant.”

But perhaps the most haunting letter of all was sent in December of 1976, two years before the murders on Camino Del Sur in Palm Springs. It was written to Edward Hutton by his father, Curtis Hutton, the man whose long-ago kindness to a motherless little rich girl earned him a $1 million trust fund that, in the end, shattered the lives of so many people.

“Dear Edward:

This is probably one of the hardest letters I have ever had to write to you. You, as my son, I love very much but as a man I cannot say you have amounted to much. Nearly 38 years old and no steady job with certainly no future to look forward to…Take a look at your own life. What have you accomplished in these past years? You have squandered money trying to be and live like a big shot….You must change your ways and improve your standard of living if you expect any inheritance from me. You must demonstrate your ability to be a good father and one that can be relied upon to contribute to the financial welfare of your children.

With love and good luck my son.”

Any reply that Edward Hutton may have made to his father is unknown.

- California: http://dujour.com/category/cities/orange-county/

- realtor: https://donaldsoneducation.com/real-estate/online-courses/

- NEXT: “Something upped the ante from grudges and tensions to a pistol fired…”: http://dujour.com/news/a-murder-in-palm-springs/2/

- New York City: http://dujour.com/category/cities/new-york/

- NEXT: “He was broke and owed money to everyone.”: http://dujour.com/news/a-murder-in-palm-springs/3/

- NEXT: “Where is the justice?”: http://dujour.com/news/a-murder-in-palm-springs/4/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/news/a-murder-in-palm-springs/