When Truman Capote Met His Swans

by Natasha Wolff | January 27, 2016 9:43 am

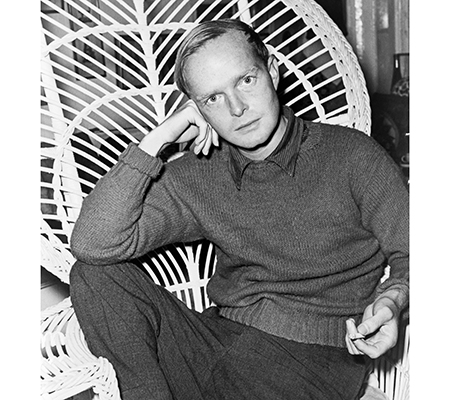

“I introduced you to him first,” Slim reminded Babe after that fateful weekend jaunt to the Paley’s home in Jamaica; that startling, stunning weekend when Babe and Truman[1] had found themselves blinking at the first dazzling sunrise of friendship, still so new that they didn’t quite understand that it was friendship, this thing that had cast a spell over the two of them to the exclusion of mere mortals. “You just don’t remember. But he was mine, my True Heart. It’s not fair hat you’ve stolen him from me.” And Slim pouted and shook her blond hair, always hanging over one eye, looking more like Lauren Bacall[2] than did Lauren Bacall, which was only appropriate, since Lauren Bacall had modeled herself after Slim. “Around the time he was working on the screenplay of Beat the Devil, Leland brought him home for dinner one night. Don’t you remember?’

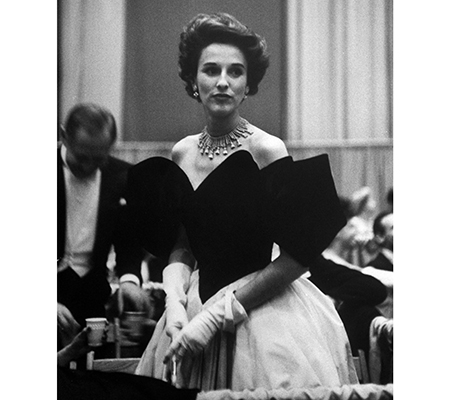

Babe Paley

“No it was I who first discovered him,” Gloria insisted with a flash of her exotic dark eyes; that flash that always threatened to expose her real origin, concealed so nearly completely beneath the Balenciaga dresses and Kenneth hairstyles—and studied British accent. “I’m surprised, Slim, that you don’t recall. It was soon after he adapted The Grass Harp for Broadway. I don’t generally go in for Broadway, naturally,” she said with an arch look at Slim, who bristled. “But I’m very glad I went to that opening night. I told you all about him then, Babe.”

“My dear, no. I invited him for the weekend, in Paris, don’t you recall?’ Pamela broke in, her voice so veddy, veddy British that they all, instinctively, leaned in to hear her (and they all instinctively, recognized the ploy for what it was, and the many times their husbands had done the same thing, only to encounter Pamela’s magnificent cleavage displayed in a low-cut Dior). “Long before any of you—back when he had just published Other Voices, Other Rooms. Bennett Cerf, you know, the publisher”—and she could barely suppress a shudder; one simply did not like to admit one knew those types—“asked me if I could entertain this young novelist of his, as he was rather nervous about reviews. You were there, Babe. I’m certain of it.”

“Ladies, ladies,” admonished C.Z., unflappable and untouchable as ever, never quite “in” but never quite “out” of their world—simple and uncomplicated, a Hitchcock blonde with a sunny smile (and a clenched, exceedingly proper Boston drawl). But C.Z., they all knew, was happier puttering around in her garden, spade in hand, or tending to her horses than she was lunching at Le Pavillon. “I don’t usually care about this sort of thing, but I do believe I was the one who introduced Truman to Babe. We were shopping at Bergdorf’s[3]. Truman is marvelous at picking out just the right handbag. You were there that afternoon, Babe.”

Truman Capote

“No, I propose it was on our yacht,” Marella said in her uncertain English; her entire manner was shy and tentative around her friends, since she was much younger than they were, never entirely sure of her place, despite her fabulous wealth and exquisite beauty—and a face that Truman had pronounced “what Botticelli would have created, had Botticelli had more talent!” “Alec Korda brought him along one summer. I believe you and Bill were there, Babe, were you not?”

Babe Paley, cool in a blue linen Chanel suit that did not crease, no matter the radiator heat of a New York summer, didn’t reply; she merely looked on, amused, as she removed her gloves, folded them carefully, and slipped them inside her Hermès alligator bag. Seated in the middle of the best table at Le Pavillon, she surveyed her surroundings.

This was her world, a world of quiet elegance, artifice, presentation. And luncheon was the highlight of the day, the reason for getting up in the morning and going to the hairdresser, buying the latest Givenchy or Balenciaga; the reward for managing the perfect house, the perfect children, the perfect husband. And for maintaining the perfect body. After all, one generally dined at home, or at a dinner party; why else employ a personal chef or two? But one went out for luncheon, at The Colony or Quo Vadis. But especially Le Pavillon, where the owner, Henri Soulé, displayed his society in the front room, spreading them out in plush red-velvet banquettes, setting the table with the finest linen, Baccarat glasses, exquisite china and silver, and cut crystal bowls of fresh flowers. They drank their favorite wine, pushed the finest French cuisine around their plates (for in order to wear the kind of clothes and possess the kind of cachet to be welcome at Le Pavillion, naturally one could not actually eat), gossiped, and were seen.

Photographers were always gathered on the sidewalk outside, waiting to snap the beautiful people inside, and Babe, tall, regal, a gracious smile on her face, was the most sought-after of all, to her friends’ eternal dismay and her own weary disdain—although the most observant, like Slim, might notice that Babe would pause, imperceptibly, if no photographer happened to be around, as if looking, or wishing, for one to magically appear.

Why was Babe Paley such a favorite? Why was she the most fussed over, the most sought out for a quick, reverent hello by those not privileged to be seated with her? She was not the most beautiful; that honor must go to Gloria Guinness, with her exquisite neck, lustrous black hair, and flashing eyes. She was not the most amusing; that was Slim Hayward, with her quips and her quick wit, honed at the feet of men like Ernest Hemingway and Howard Hawks and Gary Cooper. She was not the most noble; no, that would be a tie between the Honorable Pamela Digby Churchill daughter of a baron, ex-daughter-in-law of a prime minister, and Marella Agnelli, a bona fide Italian princess, married to Gianni Agnelli, the heir to the Fiat kingdom.

It was her style, that indefinable asset. It was said that the others had style but Babe was style. No one noticed Babe’s clothes, for instance; not at first, even though she was always clad in the chicest, most exquisite designs. They noticed her, her tall, slender frame, her grave dark eyes, the way she had of holding her handbag in the crook of her arm, the simple grace with which she pushed her sunglasses on top of her hair or unbuttoned a coat with just one hand, allowing it to fall elegantly from her shoulders into the always waiting arms of a maître d’.

What they did not notice was the loneliness that trailed after her, along with the faint, grassy scent of her favorite fragrance, Balmain’s Vent Vert. The loneliness that, despite fabulous wealth, numerous houses, children, the most vibrant and powerful husband of all her friends, was her constant companion—or, at least, had been. Until now.

“It doesn’t really matter,” Babe finally pronounced, settling it once and for all. “I’m simply so very glad to know him. To Truman!” And she raised a flute of Cristal.

“To Truman!” her five friends all echoed, and they toasted to their latest find, excited and hungrily anticipating fresh amusements galore, nothing more.

Excerpted from The Swans of Fifth Avenue by Melanie Benjamin Copyright © 2016 Melanie Benjamin. Excerpted by permission of Delacorte Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

- Truman: http://dujour.com/news/authors-writers-living-in-the-hamptons/

- Lauren Bacall: http://dujour.com/design/lauren-bacall-bonhams-auction/

- Bergdorf’s: http://dujour.com/style/in-praise-of-bergdorf-goodman/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/the-swans-of-fifth-avenue-book-excerpt/