The First Female Tycoon

by Natasha Wolff | April 25, 2022 10:28 am

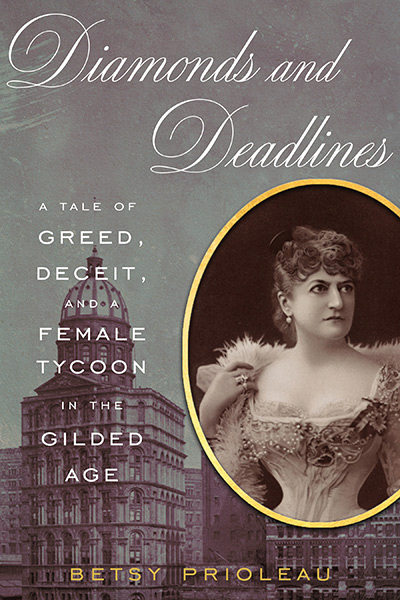

Diamonds and Deadlines: A Tale of Greed, Deceit, and a Female Tycoon in the Gilded Age[1] (Abrams) by Betsy Prioleau is the first major biography of the glamorous and scandalous Miriam Leslie, titan of publishing and an unsung hero of women’s suffrage.

Among the fabled tycoons of the Gilded Age—Carnegie, Rockefeller, Vanderbilt—is a forgotten figure: Miriam Leslie. For 20 years she ran the country’s largest publishing company, Frank Leslie Publishing, founded by her husband, which chronicled postbellum America in dozens of weeklies and monthlies. A pioneer in an all-male industry, she made a fortune and became a national celebrity and tastemaker in the process. But her name was also a byword for scandal: She flouted feminine convention, took lovers, married four times, and harbored unsavory secrets that she concealed through a skein of lies and multiple personas. Both before and after her lifetime, glimpses of the truth emerged, including an illegitimate birth and a checkered youth.

Diamonds & Deadlines reveals the unknown, sensational life of the brilliant and brazen “empress of journalism” who dropped a bombshell at her death: She left her entire multimillion-dollar estate to women’s suffrage—a never-equaled amount that guaranteed passage of the 19th Amendment. In this dazzling biography, cultural historian Betsy Prioleau draws from diaries, genealogies, and published works to provide an intimate look at the life of one of the Gilded Age’s most complex, powerful women and an unexpected feminist icon. Ultimately, Diamonds and Deadlines restores Leslie to her rightful place in history, as a monumental businesswoman who presaged the feminist future and reflected, in bold relief, the Gilded Age, one of the most momentous, seismic, and vivid epochs in American history.

Mrs. Frank Leslie was a Gilded Age superstar, an “Empress of Journalism” who ran the largest publishing company in America for twenty years and made a fortune. Her past was a closely guarded secret.

Miriam Follin was nearly seventeen, hungry in New York, and thrown on her own resources. Her choices were stark. Little wonder she came to believe that “life [was] cruel and experience [was] pitiless,” or that she lamented the plight of “the unprotected girl” in America and sought “loyal and manly protection.” Opportunities for women in the early [1850s] in Manhattan were few and thankless. Seamstresses, flower-makers, map-colorers, straw-braiders, and book folders endured “never-ending daily toil” under harsh bosses for as little as seventy-five cents a week. Volunteer societies, the House of Industry and Home for the Friendless, aided destitute women by reading them scripture and teaching these thankless trades.

Sex workers, on the other hand, earned an average of five dollars a night, and enjoyed a modicum of autonomy, especially if they freelanced part-time, which many did. An estimated fifty thousand women practiced prostitution in the city mid-century—20 percent of the female population. Successful demimondaines with sobriquets like “Princess Anna” and “Aspasia” promenaded down Broadway dressed in tight-corseted gowns of frilled ribbons and flounced satin petticoats in the latest French fashions.

There’s an off-chance Miriam resisted the call. Investigative reporters, however, entertained no doubts: She was, they charged, a conspicuous “Lais” (prostitute) who spent a “fiery youth” on the town and engaged in “wanton” doings. Everywhere “stories [were] afloat about her.”

When she looked in the mirror, she must have seen her qualifications. She wasn’t conventionally pretty; she had a hooked nose, square masculine jaw, wiredrawn mouth, and protrusive eyes. But she had filled out and boasted a figure that was the mid-nineteenth-century ideal: full, voluptuous breasts, a wasp waist, and tiny hands and feet. Plus masses of thick, dark fusilli curls. And whether she admitted it or not, she possessed a dusky, exotic “unfamiliar type of beauty.”

Her theatrical flair, fostered by New Orleans and her home life, would also have served her well. Putting identities on and off, performing a part, and “staging” herself came naturally. She had, too, the necessary do-or-die ambition, sharpened by want, fear, underclass spite, and rage for riches. There was much cash could rectify besides rent, such as shame and social exile.

But she needed guile to navigate New York’s mean streets and byzantine underworld. Dissimulation and appearance ruled in this subterranean Gomorrah, and costume was required armor—an explanation of Miriam’s celebrated fashion savvy. She quickly discarded her father’s admonitions on the “superabundance of jewelry” and ostentatious dress, and changed her name to “Minnie.”

Entry into the trade would have been easy. A Dr. Collyer on Broadway hired women to pose in “tableaux vivants,” after which the “model-artists” could arrange rendezvous with spectators at the Bowery Hotel, “no references required.” Popular assignation places, some semi-respectable, abounded: “naughty third tiers” in theaters, restaurants with private rooms, ice-creameries, concert halls, evening art galleries, and dances.

Each night an ambitious “Aphrodite” could choose from a dozen large public balls. Early in the fifties Miriam’s half-brother, Noel, remarked on her attendance: “I am glad to hear you so enjoyed the balls you attended.” But, he teased, “you did not name your escort,” and suggested several candidates: “our friend Lamp Umbrella or Mr. Denpexter or . . . [men] (of the like kind).” Clients she joked about?

He continued in a more mercenary vein. Be assured: She was “well up in the market. I cannot say less than two hundred thousand for you. If you are in luck you may catch half a million.” No mention of her Latin lessons. Susan, meanwhile, spoke often to her daughter “about [her] beaux.” They might have been their sole support. In 1854, her father abandoned all pretense of business.

Why at this moment Miriam embroiled herself in a scandal is a mystery. Contrary to her father’s admonition against “vulgar” bijouterie, she developed a passion for expensive jewelry. The recently built Tiffany might have been the catalyst—a white marble palazzo at 550 Broadway owned by the “King of Diamonds” whose show windows glittered with parures, bandeaux, rings, pendants, and corsage ornaments mounted on springs to increase the sparkle. For “Minnie” these gems assumed a talismanic significance, incarnating status, distinction, and wealth. “Within the heart of a diamond,” she maintained, was “a soul,” a glorified image of her own.

She didn’t pass Baldwin & Co. jewelers on Broadway without stopping. Inside, she met the dapper clerk, David C. Peacock, a “gay young fellow,” and one thing led to another. A bit of negotiation followed: favors in exchange for the loan of certain diamond pieces in the display case. This continued until her mother pried out the truth, and revealed a side of herself at variance with a “very refined and cultured gentlewoman.” She advanced on City Hall and demanded Peacock be arrested for criminal seduction. As of 1848 in New York State, “sexual intercourse by the defendant under promise of marriage” was a misdemeanor, punishable by up to five years in the Tombs, Manhattan’s foulest prison.

When Peacock received the arrest warrant the night of March 24, 1854, he expressed disbelief. He protested his innocence, grew “agitated and excited,” and asked to see his lawyer. Susan and the sheriff seemed to have anticipated this. Unfortunately, the lawyer couldn’t be reached, nor could Peacock “procure the $3,000 bail” (provided the sum existed) since banks were closed. Besides, the sheriff admonished, he had committed the crime of “carnal connection” with an unmarried female of “previous chaste character,” and would pay. Newspapers would publish the offense; he would lose his job and be locked in jail. Ruined.

However, the sheriff indicated, he could save himself. All would be forgiven if he married the young lady that night. Peacock recoiled and requested “time to consider the matter.” At this, the sheriff pulled him aside and impressed upon him the liberal terms: He didn’t have to cohabit with Miss Follin, support her, or see her again, and he could annul the union after two years. The lady just wanted his “name” and a marriage certificate. Still resistant, Peacock was taken from his rooms on Broome and Broadway and frog-marched to Tenth Street.

The night life in Tompkins Square was at its usual pitch when they arrived: drunks bawling “no, nay, never, no more”; a ghal crying, “Oh git out—you Mose!”; and a night cart of latrine waste drawn by Black men in bandannas lumbering by. When they reached number 319, “the mother of the girl appeared” and ushered them into a dim front room. She summoned her daughter and an awkward moment ensued. In the preparations, someone had forgotten to hire a justice of the peace. At last, Alderman Nathan C. Ely appeared on the stoop, and the ceremony began.

“Do you take this woman your lawful wife?”

No reply.

Nevertheless, the ceremony proceeded. The bridegroom sealed the “terms” with a dollar and left without a word to Miriam. From then on, the couple “passed each other in the public street without any recognition.”

Although the arrangement seemed a net loss for Miriam, there were benefits. Marriage in the 1850s offered few advantages; under the rule of coverture, women submitted to male authority and lost both “title to their earnings or property” and their independence. By living apart, Miriam preserved her autonomy and obtained marital status, which supplied instant respectability. In the world of strangers, establishing a good reputation was a crucial survival skill. And the “seduction” charge helped in another way. Since Peacock couldn’t be guilty unless Miriam was of “chaste character,” she was revirginated overnight.

Excerpted from Diamonds and Deadlines: A Tale of Greed, Deceit, and a Female Tycoon in the Gilded Age, by Betsy Prioleau. Published by Abrams March 29, 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Betsy Prioleau. All rights reserved.

“Diamonds and Deadlines”

- Diamonds and Deadlines: A Tale of Greed, Deceit, and a Female Tycoon in the Gilded Age: https://www.abramsbooks.com/product/diamonds-and-deadlines_9781468314502/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/the-first-female-tycoon/