A Dazzling Desert Rose

by Natasha Wolff | March 26, 2019 2:00 pm

After nearly 10 years of planning and construction, one of the world’s most anticipated architectural projects is slated to open to the public for the first time on March 28. Designed by the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Jean Nouvel, the National Museum of Qatar[1] is a feat of dazzling architectural and engineering bravura, the tilting contours and geometric angles of its interlocking rooftop disks unfolding along Doha’s waterfront promenade like an apparition in a fever dream. The museum presents a vision of the future that is undeniably rooted in the desert from which it grows.

The building’s striking form is inspired by the desert rose, naturally occurring crystal deposits that present themselves in desert environments, so named because the crystals fan open like flowers in clusters of radiating petal-like plates. “Qatar has a deep rapport with the desert, with its flora and fauna, its nomadic people, its long traditions. To fuse these contrasting stories, I needed a symbolic element,” Nouvel said in a statement. “Eventually, I remembered the phenomenon of the desert rose: crystalline forms, like miniature architectural events, that emerge from the ground through the work of wind, salt water, and sand. The museum that developed from this idea, with its great curved disks, intersections, and cantilevered angles, is a totality, at once architectural, spatial, and sensory.” Indeed, the building appears as one with its environment—sand-colored concrete cladding merges with Qatar’s arid desert landscape; the deep overhangs created by the intersecting disks produce shade and protect the interiors from light and heat.

Aerial view of the upcoming National Museum of Qatar designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel (photo by: Iwan Baan)

“The idea takes shape via the so-called contextual approach Jean Nouvel always adopts in his projects,” says Hafid Rakem, Ateliers Jean Nouvel’s project manager in Doha. “This approach can be defined as the chemistry and synthesis of a compound of problems relating to geography, climate, history, culture, the genius loci, and the client’s aspirations.”

The starting point for the design, and an essential component of the pre-build context, was the Old Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al-Thani (1880–1957), son of the father of modern Qatar. Built in the early 20th century and recently restored, the palace has served as a royal residence, the seat of government, and, since 1975, the former national museum. The constellation of interlocking saucers creates a ring of gallery spaces around the palace and caravansary, a central court that will be used for outdoor cultural events. “We thought of [the Old Palace] as the jewel in the necklace,” says Rakem. “Thanks to the disks, the building touches the ground lightly, unaggressively, and in correct proportions, fanning out around the palace.”

Despite the divergent architectural styles of the two buildings, the new structure constantly references and reflects aspects of the old. “The similarity with the Old Palace lies on the emotional side: The tranquility of the Old Palace’s internal courtyards is now re-created in the caravansary space within the new building. The Old Palace’s proximity and visual connection to the sea has been maintained. The sharp inclination of one of the disks—named the pearl disk—to the right of the palace’s north door was designed precisely so it wouldn’t obstruct the original facade,” Rakem explains. “In terms of museography, the palace is like a gallery in itself, a kind of flashback to a neutral past that shunned excess.”

Close-up view of the interlocking disks of the new National Museum of Qatar designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel (photo by: Iwan Baan)

The technical challenges of constructing a building composed of disks, numbering 508 in total and of various sizes and configurations, were immense. “To give you an example, the total amount of steel used in the structure of this project is the equivalent of three times the quantity of iron used to build the Eiffel Tower,” Rakem says. “Each disk is self-supporting in relation to the adjacent disks. The number of nodes and links created by the interlocking of these disks is phenomenal. All the nodes required us to enlist the computational power of supercomputers. The biggest problem we faced on the structural level was coordinating the other parts, so as to get the requisite spaces inside the building right. Every modification or movement of a structural element entailed a number of hours of high-performance computation to check that the building was stable.”

“Another technical challenge was assembling the 76,000 ultra-high-performance concrete cladding panels. Each cladding panel was specifically sized according to where it was to go,” he says. “On-site assembly was managed essentially in 3-D and to within a millimeter. The biggest problem we faced installing the cladding panels was essentially due to the different structural movements of the building during construction. We needed to make adjustments to adapt to those shifts.”

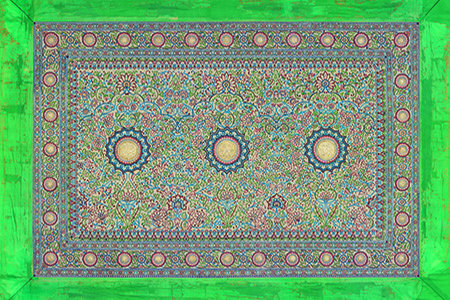

The Pearl Carpet of Baroda

The interior gallery spaces follow an undulating loop that gently rises and falls, evoking the natural floor of the desert. “The galleries were designed as a single, continuous, uninterrupted circuit, but with a multitude of sequences: a floor on a perpetual incline and warp, heights that can vary from three to 13 meters, extremely open or extremely confined volumes,” says Rakem. “The interiors are based on and extend the stresses and tensions set up by the exterior disks.”

The complex comprises 8,700 square meters of exhibition galleries, two cafés, a restaurant, a 213-seat theater, a library and research center, and children’s activity rooms. A lagoon runs along the building’s western side, while a landscaped park to the north features botanical gardens with native vegetation adapted to the region’s climate.

The building’s interlocking disks up close

The permanent galleries take the visitor on a chronological journey through Qatar’s natural, cultural, and political history, from ancient times to the present, creating an immersive experience that includes oral histories, archival images, artworks, music, storytelling, and evocative aromas. Highlights of the collection include the renowned Pearl Carpet of Baroda—commissioned in 1865, embroidered with more than 1.5 million of the highest-quality Gulf pearls, and adorned with emeralds, diamonds, and sapphires—as well as archaeological and heritage objects, manuscripts, documents, photographs, jewelry, and costumes. The outdoor spaces feature a number of artworks, including Jean-Michel Othoniel’s monumental installation of 114 fountains set within the museum’s lagoon, their streams designed to evoke the fluid forms of Arabic calligraphy, and a sculpture by Syrian artist Simone Fattal, Gates of the Sea, inspired by the petroglyphs found in Qatar at Al Jassasiya.

At once a monument to Qatar’s cultural heritage and traditions and an expression of its evolving identity in the contemporary world, the National Museum of Qatar symbolizes and makes manifest a young country’s bold aspirations.

- National Museum of Qatar: https://qm.org.qa/en

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/national-museum-of-qatar-architect-jean-nouvel/