A City Stroll with Lyndsay Faye

by Natasha Wolff | May 15, 2015 1:31 pm

From French-handbag boutiques to rarefied-chocolate stalls, few Manhattan neighborhoods are more up to-the-minute than Nolita. At first glance, standing across the street from the newly opened Helmut Lang outpost on Prince, writer Lyndsay Faye fits right in. Fishing through her handbag, she’s slender and bohemian chic, wearing RayBans and a semi-precious-stone necklace, a halter dress and Chinese Laundry shoes.

“Found it,” she says triumphantly, pulling from her bag a paperback book[1] and pointing to a passage. “They were taught to say this: ‘Abhor that arrant whore of Rome and all her blasphemies.’ That was in a children’s primer!”

On this bright yet muggy Friday afternoon, Faye and I had met at the appointed place, outside St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral at 263 Mulberry Street. It was the perfect spot to make a number of points, among them that in the mid-19th century New York City was virulently anti-Catholic and no one felt the force of that bigotry more than the Irish immigrants fleeing their famine-blighted homeland. Faye herself is descended from a woman who left Ireland during the Great Famine. “We don’t know her name,” says Faye. “Which is sad and fitting.”

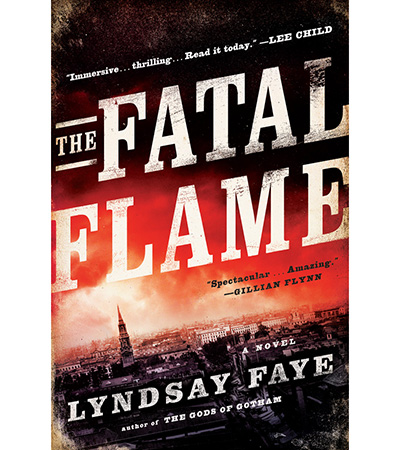

The Fatal Flame

St. Patrick’s has changed as radically as the rest of the neighborhood. Now a church offering “Basilica Bees” courtyard chats and weekly Spanish prayer group meetings, St. Patrick’s was a refuge for those thousands of traumatized Irish during the 1840s and that is the decade brought back to life in Faye’s acclaimed trilogy of novels for Penguin: The Gods of Gotham, Seven for a Secret, and, published on May 12th, The Fatal Flame[2]. They are books of finely tuned suspense and richly imagined atmosphere, with sentences such as “Our streets seemed alive as they hadn’t seconds before, omnibus drivers now free of the bone-chilling mists shrugging off oilskin capes to feel the daylight on their necks.” Faye and I spent a couple of hours retracing the steps of her vivid characters on these very streets.

“I could walk in the city all day, every day,” says Faye. She moved to New York City in 2005 with her husband when her career was acting, not writing. “I always tell people I’m a true New Yorker, in the sense that I was born somewhere else entirely. I was still doing musical theater at the time, in Bay Area California, and I always loved working with New Yorkers. We just automatically clicked. So when people were cast in New York City for big shows and I’d met enough of them, I thought we would really love it there. We came here for a two week vacation and then moved here as fast as we could.”

Her first work of crime fiction[3], published in 2009, set the mark with its bold approach. Dust and Shadow is a story, “written by” Dr. John H. Watson, of Sherlock Holmes’ attempt to hunt down Jack the Ripper in London. She then shifted her writing several decades earlier, and across continents, with 2012’s Gods of Gotham, which was nominated for Best Novel by the Edgar Awards of Mystery Writers of America and distributed in 13 countries.

There’s no question Faye possesses an eye for defining detail. “Look, they still have the green lights outside,” she says of the small glowing green lanterns affixed to both sides of the entrance of the New York Police Department’s Fifth Precinct stationhouse and tells the story of why the earliest night watch patrols, followed by the first police officers, toted green lights. We’ve left Nolita and are heading south through Chinatown by this time, another neighborhood where the characters of The Fatal Flame worked, fought and loved. The books’ main character is Timothy Wilde, a former bartender who, three years after the birth of the city’s police force, is a “copper star” who “hunts down criminals after the fact rather than stopping crime in progress as the roundsmen do.”

We make it to a barren city plaza off Centre Street that was, for 60 years, the site of Wilde’s unfortunate “employer,” i.e. The Tombs, the infamous sprawling building, modeled after an Egyptian mausoleum, that was New York’s “Hall of Justice” and “House of Detention.” Here, Faye informs me that the building was filthy and reeked, exercise was forbidden, and many a prisoner chose to hang himself on a cell hook, until such hooks were eventually removed.

Faye has compassion for the suffering seen in the city in the 19th century as well as a sociologist’s pragmatic outlook. Of the deep corruption in government, she says that the Tammany Hall politicians were the only ones to care about the Irish immigrants, those “arrant whore” worshippers. Their care for them was based on the power of the Irish voting bloc but it existed nonetheless. “They went right down to the boats and said, ‘We’re going to take care of you, we’re going to get you jobs. In return, you’re going to be loyal to us,’ “ she says. “Tammany was like a Super PAC crossed with the Mafia.”

It may seem as if the corruption, the raging fires, the high-body-count Five Points street warfare (so vividly captured in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, set right after Faye’s novels) and annihilating poverty make up a city than couldn’t be more different than today. Faye isn’t so sure. “I frankly think the worlds of 1840s New York and present-day New York are more similar than different,” she says. “We still kowtow to money and power, politics is still dirty, women and blacks still suffer more than their share of violence. The difference is that we sanitize it rather more effectively. We like being self-congratulatory, so we hide the warts behind a load of bells and whistles and bikes lanes and green space projects and Starbucks locations.”

“Unfortunately,” says Lyndsay Faye, “we’re still pretty brutal.”

- book: http://dujour.com/tag/books

- The Fatal Flame: http://www.lyndsayfaye.com/

- crime fiction: http://dujour.com/gallery/best-mystery-novels-historial-thrillers/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/lyndsay-faye-the-fatal-flame-interview/