Inside New York City’s Loft Generation

by Natasha Wolff | January 13, 2022 4:26 pm

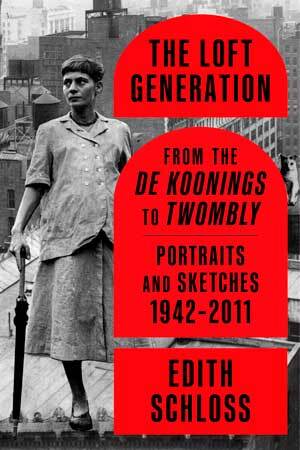

In a posthumous book, The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly: Portraits and Sketches, 1942-2011[1], edited by Mary Venturini, the late artist and art critic Edith Schloss writes about a community of American abstract expressionist painters, musicians, photographers, dancers and artists who took up residence in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood in the 1940s and 1950s. Artists such as Willem and Elaine de Kooning, John Cage, Francesca Woodman and Cy Twombly are examined in this captivating book. In the below excerpt, we explore the private lives of these creative talents.

When I was living alone in the loft, I often went to eat in the Horn and Hardart Automat, on Twenty-Third Street next to the Hotel Chelsea. I would often meet Rudy there, as he loved to observe the old ladies who would sit for hours nursing a single cup of coffee. At that time the New York City transit system ran an advertising campaign, choosing a “Miss Subways” each month from the pretty secretaries and newcomers to New York. Her smiling photograph and a brief biography were put in all the trains. Rudy chose a “Miss Automat” each month. He bought snacks for the old lady with the flowery hat and sneakers he had chosen secretly, who had to make do with a Social Security pittance. Sometimes the old people put sandwiches in their bags for others. The Automat, with cheap, nourishing food and its slogan “Less Work for Mother,” was a home away from home for us loft dwellers as well.

Because Elaine refused to cook, she and Bill always ate at the Automat. One day I saw the two of them alone together there. It was the first time Elaine talked to me. Now she was not the rich patron from uptown, but just Elaine, née Fried, from Brooklyn, the former art student eating her meat and potatoes.

She was a picture of the 1940s. Her bangs were rolled in, as was her shoulder-length pageboy bob, like a movie star’s. Her wavy reddish hair was held back by large white plastic daisies on bobby pins on each side of her face. Under finely arched brows her eyes were attentive and a little prominent. Her full, pretty mouth, always at play, was carefully outlined in lipstick red. She wore a clinging turtleneck sweater, and her waist was held tightly by a wide cinch belt over a ballerina skirt. This tightness and neatness was the style of the times, but not common with art world women. The purple of the high-heeled, all-encasing suede shoes against blue stockings was unusual. She was downtown smart, or street chic as it is called now. And she had poise.

Rudy and Elaine thought this could be put to use. His inheritance had run out, and he was trying his skill as a fashion photographer. But to get a job he needed to show samples and so, naively, he and Elaine went to Klein’s on Union Square and bought a batch of fancy dresses. Hiding the price tags in their folds, she posed, nostrils and skirts flaring. Then both of them took the dresses, price tags intact, back to Klein’s and got their money back. But there was something not quite right about the photographs. Whether Elaine’s haughtiness was too mocking or Rudy had not thought of airbrushing the wrinkles, he never got the job. The strength of Rudy’s style has always been its truth. But if these photos still exist, they are a record of Elaine’s sharp New York bearing.

Her talk was smart and refined too. She had a way of enunciating carefully with a pronunciation quite her own, which didn’t quite cover the Brooklyn accent under it. No one else had that special way of saying “Oartist” or “World of Oart”—meaning the New York world of art, the only one that existed for Elaine—which still echoes in my ears. She spoke with a bright, “cultured,” knowledgeable air, which fooled the men who adored her, but not other women. Though I had left school at sixteen, I humorlessly prided myself on my civilized European background. Bill made no bones about being self-taught, but Elaine, who had only gone through high school before a few years of art school, put on such highfalutin intellectual airs that it irritated me. I didn’t appreciate her lively mind then.

Only when Bill spoke did Elaine fall silent. She listened demurely. In the Automat that day, their heads were turned toward each other. I see it still. Has there ever been a wife who was never once bored with her husband? She had a wonderful trust and respect that she maintained forever. Her Sylvia Plath hourglass silhouette was conventional, and I thought their marriage was conventional too. Why couldn’t they just live together like the rest of us artists did?

Rudy told me that Bill had said to him, “When you have a girlfriend, it takes up too much time. You have to talk to her, you have to take her home in the subway—and then you have to ride home yourself—two hours there, two hours back. Talking at least six hours (lovemaking was implied) and then you paint sixteen hours. So when do you sleep?” But it was not quite like that. Bill was the son of plain Dutch working-class people, Elaine the daughter of honest American immigrants, and both were brought up to do the right thing. Nor did either of them ever want a divorce, despite everything.

In those early days they were devoted to each other. They listened to each other all the time. Elaine remained devoted to Bill all her life, but she demanded constant attention, which was exceedingly difficult for him. Bill in his own particular way also remained devoted: he quoted Elaine’s opinions long after they ceased to live with each other, and Elaine quoted his, always.

How much was his in what he said? Wasn’t it Elaine who found the poetry in his words? Said raw, they could be puzzling—was it just lack of background, wily playing dumb, or a genuine directness? I was never sure, nor was I supposed to be. But Elaine knew best. Wasn’t it Elaine who wrote down all Bill’s remarks, and the famous lecture at the Modern in which he defined space as what was between his arms when he spread them lying stretched out? And those great titles of the paintings, didn’t they think them up together?

Elaine and Bill were desperately poor in those days because Bill had made a choice. He had been a wonderfully exacting craftsman. The cubicle or inner room of their loft and the famous shower stand at 116 were made with painstaking skill. The pieces were perfectly fitted, the paint put on—layer after layer—and smoothed down to a silken finish. He never took on anything he could not carefully bring to an end and be paid for.

Frank Safford, Edwin’s Harvard friend, and his wife, Sylvia, commissioned Bill to do easy chairs for their beach house in Wading River. They were beautifully original, with curving white armrests, like elephant tusks, and surfaces in purple and yellow, in a style postmodern before its time, which Bill had invented. Bill was always a perfectionist. Besides doing odd jobs as a carpenter, he also did posters and an ad in a glossy magazine for a brand-name gasoline, of faceted windmills in bright greens, oranges, and pinks, which I kept for a long time. Somehow he and Elaine managed to get along on this. Then one day he was asked to do some window displays for a fancy department store. When he finished, they offered him window designing as a steady job, something to the tune of $100 or $150 a week, a tremendous sum then. He and Elaine could have lived off this royally. But he thought about it. “As a window decorator, I would do a good job,” he said, “but then how could I do a good job as a painter at the same time?” It was one or the other. He had made a choice. He was a painter, and he would get by. He chose to do painting and did nothing else.

Not everybody was able to make that kind of decision. They painted and had a job on the side too, always an art-related job. Rudy took photographs for galleries, Elaine and I did art reviews. Some people made frames, others transported paintings from loft to gallery and back. In the end, almost everyone became a teacher, which was not always good for them. When someone chose weighty words, pontificated, and took himself too seriously, you knew at once he had become a teacher. Norman Rockwell’s son Peter once told me that Norman would not teach, because, as he said, “You give away your secrets.”

Just once there was a teaching job Bill was happy to accept. “Guess what,” he said excitedly to Elaine when he came home one day. “I got a job teaching. I got a job teaching at jail!”

“That’s nice,” she said soothingly, and went on painting.

“But aren’t you excited?” cried Bill. “It’s a job at jail!” She was still not excited. Then he explained it to her carefully—a friend had arranged for him to give a lecture at “Jail University.” Afterward he told us about his only teaching experience, at Yale University. “So I stood there and told them about everything, everything I knew and thought about art. I talked and talked to them very sincerely, I went on and on. Then I noticed how quiet they were. I suddenly looked at them. All of them, they didn’t look at me—every one of them was staring out the window. They looked up at the sky with nothing in their eyes, like saints in a Renaissance picture. This politeness, this lack of interest, this total daze . . . it was fantastic.”

“The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly: Portraits and Sketches, 1942-2011”

Another way of getting by was to receive a grant handed out by a benevolent foundation. It gave you prestige but usually only helped out for one year—a one-shot event, not often bestowed on people who deserved and needed them. Those with some kind of academic standing were always preferred. Many great artists never got them. Arnold Schoenberg, for instance, old and struggling in California, never got a Guggenheim. John Cage got one after his twelfth try. And after receiving a grant, many grantees were never heard of again.

It is amazing that a painter like Bill never received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He applied for it once because Buckminster Fuller, who had been told they were looking for avant-garde artists, had brought up his name and told Bill that this was his chance. Bill hated to fill out the forms, but most of all, as he put it, “I hate having to bother decent people. I don’t like to waste their time writing those recommendations.”

When I wanted to apply for a Guggenheim, I thought of asking Bill, already very famous, to be one of my sponsors. As I didn’t have his address, I wrote to Elaine, explaining why. She sent it back with a curt note: “Bill and I never got a Guggenheim so why you. But if you want to fill in all those dreary forms, go right ahead.”

But whether you lived off your work or not, “What is necessary is a little recognition,” said Elaine, “even a little keeps you going.” This came up in regard to the painter Earl Kerkam, who secretly elaborated a Cubism all his own. Embittered by lack of interest in his work, he became a recluse. When he was finally taken up by Tom Hess of ARTnews—because Elaine suggested it—it was too late. Kerkam was arid, old, and ill.

“It’s okay not to be pushy,” Elaine said, “but a little bit of appreciation by your peers goes a long way. You have to have a few people see what you are doing once in a while, or else you shrivel up.”

If you stuck to your work you had to make do with a loft, but if you stuck to a job you lost the art but had lots of comfort. The new commercial artists despised and envied their former pals.

Bill, long celebrated downtown and now celebrated uptown as well, once met a former painter at a party. The man was now a successful commercial illustrator. He had an easy but not very fulfilling life. That night he was drunk. Elaine saw how he suddenly advanced on Bill, a heavy brass candlestick in his hand.

“You bastard!” he yelled. “It’s not just me who has sold out—you, with all your phony stuff! It’s easy—you just go on slinging the paint.” And he hit him. “Take that, you phony!”

Bill was sitting in an easy chair. He did not move. He sat there, still and silent, blood running down his face while the man went on hitting him. Finally people pulled the crazed attacker away. Elaine said Bill sat there with an utterly astonished face without moving, not believing such white-hot hate could be streaming out at him.

Very few people bought his paintings at first. There were Janice Biala and her husband, Daniel Brustlein, painters themselves. They bought his fine Ingres-like silverpoint drawings and some of the oils. Then there were the Auerbachs, Edwin, and Rudy. Marie Marchowsky, the dancer, gave him a commission for a backdrop, and John Becker showed paintings of Bill’s once in a while in his gallery, the only one of modern art in Manhattan in the 1930s. Fairfield would occasionally buy paintings, and Bill just gave to his friends.

The few sales were never enough. Bill sometimes had to come over to our loft at 116 to borrow money for kerosene, or even for food. I didn’t like it. Dr. Frank Safford’s wife, Sylvia, didn’t like it, and once said, “I’d like to see the de Koonings pay in cash once in a while, not always with paintings. After all, who does Bill think he is, Gauguin?” Little did she know.

When visiting Rudy in his studio, I saw Bill come in and unwrap a painting he had brought for Fairfield. It was about ten by twenty inches, in wonderful cadmiums and slashes of green, inhabited by strange, curvy cuttlefish shapes and enigmatic taut insets—half interior, half landscape. Bill laid the piece of paper—beautifully covered with paint—on the table. Fairfield laid his checkbook next to it. Then he bent down and wrote out a sum. It was something like $150. I was thrilled. I had never witnessed such a transaction. It was the first time I saw a real live sale of a real live painting.

Another painter told Peggy Guggenheim about Bill, and she invited him to be in a group show of new talent at her famous Art of This Century gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street. Bill went into a fever of work. To meet the deadline, Bill and Elaine carried the painting uptown when it was still wet. But when Bill got back downtown, he got into a state worrying about it. He was not satisfied with it, and just before the opening he went back, took it off the wall, and brought it home again to work on it some more. In those days it was as difficult for him to finish a painting as it was to start it.

Later, in 1948, Bill’s friends convinced Charlie Egan, who had a tiny gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street, in which he slept, to give Bill his first one-man show. Charlie had an eye for what was then unusual. He had shown Yves Tanguy, Isamu Noguchi, and Joseph Cornell, who were not entirely unknown, but were relatively new to the few ordinary gallerygoers.

Bill’s first solo show was a wonder to his friends, who kept going back and back again to the smallish intense paintings, now—away from the studio—on clear walls. But there were no buyers, and there were no reviews. In the end, Emily Genauer mentioned the show, perhaps in the New York Post. She complained that de Kooning painted “abstractions with brash colors.”

“Someday you’ll be in the Modern,” we used to say to Bill encouragingly. “Oh yeah, you think so?” he asked, and cocked his head. We could not really imagine it, but he knew.

Excerpted from The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly: Portraits and Sketches, 1942-2011 by Edith Schloss. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by the Estate of Edith Schloss. Editorial work copyright © 2021 by Mary Venturini. Foreword, Chronological Biography, and Glossary of Names copyright © 2021 by Jacob Burckhardt. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Mira Schor. All rights reserved.

- The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly: Portraits and Sketches, 1942-2011: https://www.amazon.com/Loft-Generation-Koonings-Portraits-1942-2011/dp/0374190089

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/loft-generation-book/