The Story of American Idols

by Natasha Wolff | July 8, 2022 7:34 am

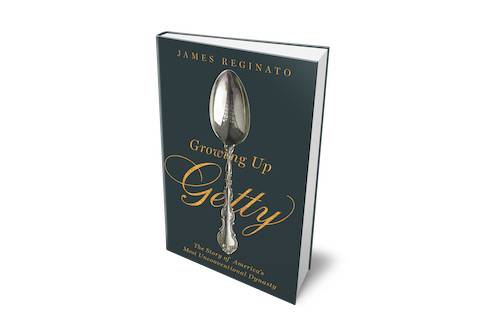

In Growing Up Getty: The Story of America’s Most Unconventional Dynasty[1], author James Reginato offers an enthralling and comprehensive look into the contemporary state of one of the wealthiest—and most misunderstood—family dynasties in the world. Now spread across four continents, a new generation of eccentric and even outrageous Gettys are bringing this legendary clan onto the global stage in the 21st century. Through access to J. Paul Getty’s diaries, never-before-seen love letters and fresh interviews with family members and friends, Reginato takes us deep into the lives of this charismatic and elusive clan. In the accompanying excerpt, Ann Getty hosts an elaborate dinner party at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Temple of Dendur as the fate of Getty Oil hangs in the balance.

The cover of Growing Up Getty: The Story of America’s Most Unconventional Dynasty

As 1983 drew to a close, the simmering tensions between the board of Getty Oil and Gordon exploded. The trigger had been pulled on November 14, when the lawsuit in his nephew Tara Getty’s name was filed in Superior Court of Los Angeles County. This action also compelled Harold Williams, the president of the J. Paul Getty Trust, to go into high gear: he had to protect the value of the 12 percent of the stock that the museum owned.

Gordon and Ann flew from San Francisco to New York to meet with new, high- powered members of the Getty Oil board who had been nominated by Gordon but recruited by Ann—including Laurence A. Tisch, chairman of the Loews Corporation, and A. Alfred Taubman, the Detroit real estate developer who had recently acquired Sotheby’s auction house.

With the apartment at 820 Fifth Avenue not yet ready, Ann and Gordon ensconced themselves in a suite at the Pierre Hotel, formerly owned by his father. The fate of Getty Oil hung in the balance. The stakes couldn’t have been higher. Just then, Ann gave the most fabulous party New York had seen in ages.

J. Paul Getty and Margaret Campbell, Duchess of Argyll (Pierre Manevy/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The evening of November 30, a Wednesday, she put on a white satin Dior[2] gown embroidered with gold and welcomed two hundred guests to a dinner in the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art[3], to celebrate Gordon’s fiftieth birthday. In addition to a squadron of Gettys, including Gloria, Aileen, Ariadne, and Mark, there was a contingent of forty leading San Franciscans, including the indomitable Denise Hale, all of whom Ann had flown in. Among the notable New Yorkers[4] and Europeans were Brooke Astor, Vicomtesse Jacqueline de Ribes, Lynn Wyatt, Nan Kempner, Bianca Jagger, Ahmet and Mica Ertegun, Carolina and Reinaldo Herrera, Robin Hambro, Pat Buckley, and, of course, Greek-born financial advisor Alecko Papamarkou, Ann’s constant companion.

After a performance by violinist Isaac Stern, Luciano Pavarotti rushed over from the Metropolitan Opera as soon as the curtain fell on his performance of Ernani, and surprised everyone with his rendition of “Happy Birthday.”

“It was one of the best parties ever,” proclaimed Mrs. Buckley. Five nights later, Buckley presided over the other most glamorous party of the season, under the same roof—the opening of the Yves Saint Laurent[5] retrospective at the Met’s Costume Institute, where Gordon’s late sister-in-law, Talitha, was extolled.

The very next night, many of the same guests, and about a thousand others, filled Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, to hear soprano Mignon Dunn of the Metropolitan Opera give a recital featuring eighteen songs from The White Election, composed by Gordon Getty, which incorporated poems by Emily Dickinson. The drama was only beginning. A couple weeks later, J. Hugh Liedtke, chairman of Houston-based Pennzoil, announced a tender offer for 20 percent of Getty Oil’s outstanding stock. The company was officially in play.

Sabine Getty on the family’s yacht, Talitha (Jason Schmidt, Trunk Archive)

In San Francisco, Ann and Gordon had barely unpacked; they rushed back to New York, checking into the Pierre again. An enormous cast of characters representing all sides of the deal took up their positions in the suites and conference rooms of every leading hotel, law firm, and investment bank in town. Following frantic negotiations, Pennzoil raised its offer—it was now a $110 per share leveraged buyout. Considering that GET had been trading at around $50 a year before, it was, in many eyes, a great deal for shareholders—Gettys and non-Gettys alike.

Then things hit an impasse. Liedtke was frustrated because he had been able to deal only with Gordon’s battery of bankers, lawyers, and advisors. He announced he would pull out if he couldn’t meet with the man himself. “I don’t want them telling Mr. Getty what I think or what I’m offering. I want to sit right across the table from him and tell him myself so there won’t be any question,” said the tough Texan, according to The Taking of Getty Oil by Steve Coll.

No way, Gordon’s people responded.

Liedtke pondered how to get a message directly to Gordon. On December 30, seeking advice, he phoned fellow Houstonian Fayez Sarofim, a stock fund manager and investment advisor who also owned a big block of Getty Oil. Though he was now a well-established Texan, the Cairo-born Sarofim descended from Egyptian nobility. His ancestry, combined with his tight-lipped inscrutability, had earned him the nickname “the Sphinx” in financial circles. (Though the Sarofim heritage stretches back seemingly to the pharaohs, the family name today is perhaps most widely known thanks to Fayez’s live-wire daughter, Allison, who throws New York’s most extravagant and exclusive annual Halloween party in her West Village townhouse.)

Joseph and Sabine Getty at home (Simon Watson)

Sarofim told Liedtke he knew how to handle it: he would call Papamarkou, who could in turn call Ann to ask her to pass Liedtke’s meeting request to Gordon. It worked. Close to midnight on New Year’s Eve, the chairman boarded the Pennzoil corporate jet in Houston, bound for New York. His meeting with Gordon was set for New Year’s Day. Liedtke turned his Texan charm on Getty, recalling his wildcat- ting days in Oklahoma and his acquaintance with J. Paul Getty. His son agreed to a $112.50 a share offer from Pennzoil. In essence, Ann and Alecko had gotten the biggest corporate acquisition in history back on track.

Then the whole thing jumped to a different track. Gordon’s niece Claire got a judge to temporarily block the deal, so she and other family members could evaluate it. During the two-day pause, Texaco chairman John K. McKinley swooped in and offered $125 a share. After wild, round-the-clock negotiations (and after Claire dropped her opposition), Texaco officially won the prize when the papers for the $10 billion deal were signed around 3 a.m. in Gordon’s suite at the Pierre.

Pennzoil promptly sued Texaco, claiming it had a deal with Getty Oil even if the contracts weren’t signed. Thanks to a clause that Gordon had requested in the negotiations—in which Texaco indemnified the Getty Trust and the J. Paul Getty Museum against any lawsuits that might arise from the sale—the Getty family was not a party to this suit; they banked their billions. After a jury in Houston decided there had been a binding agreement, Texaco was ordered to pay Pennzoil $10.5 billion in damages, the largest jury verdict in history. The two oil companies battled for four more years in court over the judgment. Eventually, Texaco paid a $3 billion settlement to Pennzoil, and went bankrupt.

Getty Oil ceased to exist; twenty thousand employees lost their jobs. Oil prices plunged. Having cashed out at the top of the market, the Getty family’s $4 billion fortune was secure.

That’s capitalism—as Gordon explained to an auditorium of University of San Francisco students a couple of years after the sale. “I’m in favor of takeovers, the more hostile the better,” he declared. “I like to look at takeovers, and hostile takeovers in particular, as efficiency and economic evolution in action.”

Whatever the explanation for their good fortune, the Gettys were, once again, on top. Gordon Getty was the richest man in America.

- Growing Up Getty: The Story of America’s Most Unconventional Dynasty: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Growing-Up-Getty/James-Reginato/9781982120986

- Dior: https://dujour.com/gallery/dior-new-looks-book-photos/

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://dujour.com/culture/the-metropolitan-museum-of-art-nyc-celebrates-150-years/

- notable New Yorkers: https://dujour.com/culture/andy-warhol-studio-54-photos/

- Yves Saint Laurent: https://dujour.com/style/yves-saint-laurent-assouline-new-book/

Source URL: https://dujour.com/culture/growing-up-getty-the-story-of-americas-most-unconventional-dynasty/