Jon Crumiller has never killed an elephant. He is as upset as anyone over the continued slaughter of the animals in Africa for their tusks. But he does own hundreds of pieces of antique carved ivory—in the form of rooks, knights, queens, kings, bishops and pawns. For that, he’s been compared by online commentators to the killer of Cecil the Lion. “People love to have a villain,” says Crumiller, a collector of old chess sets, most dating to the 18th and 19th centuries.

Crumiller bought them not because of any particular obsession with ivory—he’s a chess player. His cache of beautifully fashioned games, half of which are non-ivory sets, includes German, Indian and Chinese examples. The COO of a consulting company in Princeton, Crumiller legally purchased all of these antiques. At auction, until recently, they went for $10,000 to $70,000. But as of 2014, under a sweeping new law in New Jersey that bans the sale of ivory in the state, even of antiques, he would be breaking the law and face fines if he ever tries to sell them. “The value of my sets is now effectively zero,” he says.

The New Jersey statute heralded the beginning of a wave of such bans, all intended to stem the global trade in ivory, which is taking a deadly and possibly species-exterminating toll on elephants. “People need to understand that ivory is better on elephants,” says John Calvelli, executive vice president of public affairs at the Wildlife Conservation Society and director of its 96 Elephants campaign, named for the estimated 96 elephants killed daily by poachers for their tusks. The entire population of African elephants—many of which are horrifically butchered, leaving calves orphaned—has plummeted from 1.2 million in 1980 to 400,000 today. “By treating ivory as a commodity, we are moving inexorably toward the extinction of a species,” says Calvelli.

The Society is part of a broad coalition of more than 225 organizations that have helped enact similar bans in New York and California, restricting sales to antiques that are at least a century old and have small percentages of ivory. In November, billionaire Paul Allen poured almost $2 million into supporting a similar voter initiative in Washington state that passed with 70 percent support. Advocates hope for success in other states. There are also proposed new Obama Administration rules that will ban sales of ivory among all 50 states, unless an item can be proven to be more than 100 years old and meet certain import requirements. In 2014, Hillary Clinton called for a complete ban on any sales anywhere in the U.S.

Ivory-ban supporters say that shutting down trade of what is currently legal will destroy the value of the material, taking away any incentive for poaching. Many art and antiques dealers and aficionados say that the laws are an overreaction and infringe on the property rights of people who bought pieces legally—items that were made when elephants weren’t endangered. What’s certain is that hundreds of thousands of antiques, including family heirlooms, are affected. Taylor Swift, for instance, who owns a 1913 Steinway piano (all of which had ivory keys before synthetics were introduced in the 1950s), would not be able to sell it across state lines if the federal rules go into effect. Those new rules would also prohibit the commercial importation of any antiques containing ivory. Edmund de Waal, best-selling British author of The Hare with Amber Eyes, about his family’s collection of Japanese decorative netsuke, many in ivory, would not be able to sell his pieces to an American collector. And American museums, as of 2014, are no longer able to import important historical works containing the material—such as a suite of Phoenician carved ivory pieces owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art—for their permanent collections.

“This is nothing short of cultural terrorism. It’s a form of censorship because of the material from which it is made,” says antique-ivory dealer Scott Defrin of New York’s European Decorative Arts Company, whose business in antique ivory carvings has plummeted. “People are very nervous about buying. There isn’t an antique dealer that wouldn’t support the fight against poaching, but Americans are not the criminals here. We are not the poachers.”

Estate lawyers say that high-net-worth individuals would be wise to learn about the changes. Possession isn’t illegal and pieces can be passed down to heirs, but the value may be gone. “What’s going to happen when individuals try to donate their art in order to get a tax deduction if the pieces are worth zero?” says Amy Altman, an estate-planning attorney at Meltzer, Lippe, Goldstein & Breitstone. “I think it’s penalizing the wealthy for absolutely no reason.” Defrin adds that appraising objects for tax or inheritance purposes is almost impossible when the market for such items has been eradicated. “The ripple effect of draconian government intrusion is devastating to a venerable trade where there’s no culpability among the antique dealers, auctions, collectors and museums,” he says.

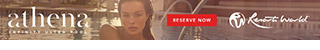

Exhibit A for such penalties is New York’s Sapir family, which owns a prestige slice of Manhattan real estate, including until recently the Art Deco–style 11 Madison Avenue tower. When its patriarch, one-time billionaire Tamir Sapir, died in 2014 at the age of 67, he left behind five children and a collection of 3,000 European ivory antiques. Sapir, who at one time planned to create his own museum to display the works in an eight-story Fifth Avenue mansion, felt they were ironclad investments. “I am very conservative with my money and therefore don’t risk it on the stock market or in hedge funds. It is safer to invest it in ivory,” he told a newspaper in 2007. According to dealer Defrin, who sold numerous pieces to Sapir, the businessman spent at least “in the area of $5 million on his collection.” (Sapir ran foul of the feds in 2009, after his $26 million yacht was found to have a stuffed African lion, zebra skins and a jaguar skin rug on it; he paid a $150,000 fine.) Do his heirs now wish he had invested his millions differently? A representative for the family declined comment.

Opponents of the bans question whether these moves will actually reduce poaching. “The U.S is not a big problem as far as importing illegal ivory,” says Dan Stiles, a wildlife-trafficking consultant who recently completed a study on the subject for the Natural Resources Defense Council. While he found that a number of stores in California, including one in Beverly Hills, are selling what he believes is illegal carved ivory—works that are fraudulently labeled as antiques—Stiles contends that less than 1 percent of poached ivory makes it to the U.S. This is partly due to existing laws and partly to lower prices. According to a co-founder of the Elephant Protection Association, ivory in China, the world’s number one importer, can currently command around $1,000 to $1,500 a pound, while in the U.S., its value is around $200 to $250 a pound. “There were laws on the books in the U.S. that were sufficient for arresting people for illegal ivory—they were just not being enforced properly,” Stiles says. “I honestly think these new laws are symbolic.”

The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Calvelli counters that “any market is too big of a market” and that the prohibitions tackle the challenge of differentiating old from new ivory, especially because many sellers of illegal ivory make it look aged. “By sight, you can’t tell the difference,” he says, adding that the U.S. can lead the world by example.

What many on both sides of the controversy agree on is that prices will fall. “If every state legislates that it is illegal to sell ivory, there will no longer be a market,” says Mark Winter of Ivory Experts, an antiques-appraisal company. 1stdibs, the online decorative marketplace, says it’s begun scrubbing listings from its site for antiques that contain ivory. Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s will only sell antique ivory pieces that are at least 100 years old and contain less than 20 percent ivory. (According to Christie’s cultural-stewardship policy, “We believe that the sale of these culturally significant works of art does not contribute to the current illegal elephant-ivory trade.”) If interstate sales are completely banned, some antiques dealers say it’s difficult to imagine that a strong black market will develop; most garden-variety lovers of antique ivory walking sticks, old pianos and cabinets with ivory inlays are simply not going to be motivated enough to risk illegal purchases. Crumiller, who’s watched the sales of chess sets at auction drop drastically, says the absence of people rushing to unload ivory pieces in the face of possible new bans is due simply to the fact that very few people want to buy something that could soon be valueless.

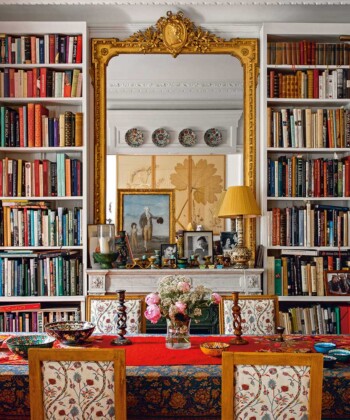

The move to rescue elephants by implementing these laws comes at a time when many in the interior-design world are still in thrall to the recent craze for using exotic animals as decor, such as taxidermied specimens from Parisian company Deyrolle or Manhattan store Creel and Gow. “I recently finished a project on the East Coast where we displayed large Victorian vitrines filled with an unusual array of exotic birds in various forms of flight and repose,” says top interior designer Martyn Lawrence Bullard, whose well-known clients have included Elton John. “Knowing [their] provenance and the age associated with them—the 1880s—I was fine to use them in my interior, much to my clients’ delight, might I add.” Collectors of these pieces may do well to consider whether some of these animals could one day become subject to new restrictions and bans as well.

“Money is not the most important thing in life, and ultimately the elephant population is more important than money,” says Crumiller. “The bans on antique ivory are a nice symbolic gesture. I think [the activists’] hearts are in the right place. But they’re not going to save a single elephant. The only way to do that is on the ground, at the point of poaching—by force.”