Sacré bleu! I forgot my beret back on land!

Surely there’s no greater sin to commit upon boarding a cruise filled with French passengers, steered by a French captain and owned by a French company. We begin in Galway, Ireland and are set to swing by the coast of Scotland before ending in Iceland. But escalating this trip to a French New Wave-level of drama is another problem: My bags are not bulging with all-black ensembles, but blues, greens, even a dress in purple. We haven’t left the dock and already I’ve failed as a Parisian.

For the love of Depardieu, what am I to do? To start, I should probably drop every stereotype and cliché rattling around in my brain (check)—and then proceed to eat, drink and frolic on land like any good little cruise ship virgin.

But, “cruise ship”—that phrase doesn’t conjure up the right images. Le Soléal is a luxury yacht, the newest in a four-strong fleet operated by Compagnie du Ponant, the only French cruise line. Less known in the States than, say, Royal Caribbean, Ponant is quite popular elsewhere, and it celebrated its 25th anniversary last year. With only 132 staterooms and suites, Le Soléal is less cruise ship than petite luxury hotel on the sea. There are no snaking lines (not even to board or disembark), it’s impossible to get lost (passengers can walk from bow to stern in three minutes) and, most notably, itineraries feature unusual destinations not usually explored by behemoth boats. Carnival or Costa Concordia, this is not.

What Le Soléal does have, I’ll discover during this six-day journey, is the best bread outside of Paris. Croissant, baguettes, the pre-meal bread always skipped by people with irritating levels of self-control. The secret lies in the “type 55” flour, ferried aboard from France. The pastries are consistent, but the chef occasionally picks up other food from local stops. Everything’s fresh as can be, from breakfast eaten in-room (poached eggs accompanied by Peugeot salt and pepper shakers, a nice touch) to elaborate lunch buffets.

The dining room onboard Le Soléal

Dinner the first night offers the choice of grilled kangaroo fillet with flat green beans, mashed lemon carrots and saffron bird pasta. The waiter likens the meat to goat; I order it medium-rare. For dinner the following night, there’s an appetizer of sea urchin scrambled eggs with codfish fritter; a third night offers lamb loin crusted with wasabi and macadamia nuts.

In addition to the food, however, everything else in the dining room feels equally refined. Perhaps it’s the adjacent passengers, effortlessly glamorous and dressed to the neuf, murmuring about their days between sips of wine. (Everyone sounds brilliant when you can’t understand a word they’re saying.)

One night the post-dinner entertainment is a concert by Celtic folk-rock band Tri Yann, fronted by a man, Jean-Louis Jossic, with the follicles of Einstein and the fashion of Jagger. He introduces one song in French with a long explanation that gets plenty of laughs, but explains it to English speakers succinctly: “This is a story about a famous dolphin.”

A room onboard Le Soléal

I head to bed wondering how Flipper made it all the way to France. My room’s sleek with white walls, white lamps, white leather headboard, white TV and heavy curtains to block the sun which, on certain routes, can hang for 20 hours a day. (Also of note, there isn’t a single bag of chips or can of cashews in the mini bar. As soothing distractions, there are L’Occitane products in the bath and also some stunning fake flowers—quite pricey, I confirm later, made by Emilio Robba. Real flowers aren’t allowed for contamination reasons.)

The cliffs of Mull

This route, though, forgoes the deep freeze in favor of warmer expeditions. In Ireland, we disembark for Donegal Town, where a guide says it’s “very, very unusual to have the sun shining” (even in the summer)—and yet here it beams as passengers slip into tourist mode, snapping photos of cemeteries and observing a fraction of the 120,000 farms in the country. The following day it’s off to the Inner Hebrides, a group of islands off the west coast of Scotland. The small island of Iona, three miles long and only reachable from the Isle of Mull (pictured above) by ferry, is also experiencing a rare bit of good weather, which makes touring the 13th Century nunnery and Iona Abbey, a structure pivotal to the rise of Christianity, positively mesmerizing.

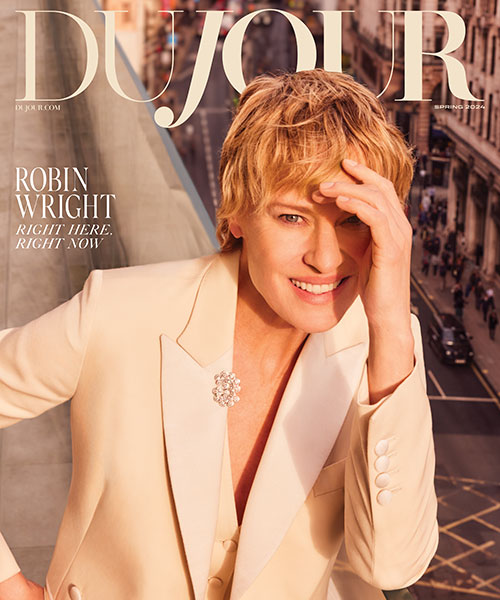

Tobermory on the Isle of Mull in western Scotland

Back on Mull, it’s over to the candy-colored capital called Tobermory, home to both a famous distillery and an Internet-famous cat. The countryside teems with shaggy Highland cattle (they have bangs!) and Hebridean sheep, while the rich surrounding seas are home to seals, dolphins and minke whales. Noah would need a few arks to evacuate this place.

After a full day and night at sea, we travel to the Westman Islands adjacent to Iceland, docking on the largest one, Heimaey, where in 1973 a volcano erupted and forced the entire island population to evacuate and leave behind homes buried in ash. They rebuilt, and it’s well-recovered now as a main fishing port. Via another nimble boat we circumnavigate Heimaey and observe the uninhabited islands, which resemble giant thumbs pointing up from the sea.

After five days at sea and with a flight home on the horizon, I’m more attached to all these tiny islands than I imagine I’d feel to more popular Dublin or Glasgow or Reykjavik. I saw the appeal of sailing against the usual currents.

Compagnie du Ponant

Le Soléal and her sister ships sail to seven continents, with itineraries ranging from immersions in the Antarctic to the “Plain of Lords” in Burma to the fjords of Norway (though, of course, not all in the same trip). Rates vary according to location and length of stay.