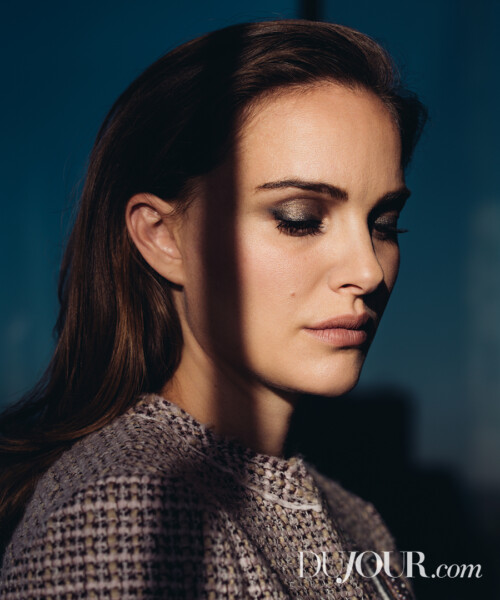

There was something endearing about the statement dress that Natalie Portman wore to a press day in New York this October, puffed dramatically at the shoulders and tenting over her pregnant belly. In a suite buried deep in the Peninsula Hotel—with large cardboard Jackie cutouts scattered around the premises, and even larger security guards around each corner—Portman offered an unsmiling handshake.

I realize that using the word “endearing” to introduce a powerful Hollywood actress—one so reputedly brainy, no less—and then going on to describe her outfit, is tempting wrath from the gods of both feminism and formulaic writing. But when I saw this (reasonably) tired celebrity sitting in a funereally quiet, plush carpeted room, all dressed up for the reporters and ready to answer their endless questions about process and inspiration, the scene couldn’t help recalling the isolated yet public world of the woman in the film we were there to discuss. The dress was endearing like the suits that late night talk show hosts continue to wear on air—archaic in an age of the ubiquitously casual, an entertainer’s gesture of respect for the stage they’ve been given. It was about showing up and putting on the designer dress with the silly puffy shoulder when she really could have just worn sweatpants. Waiting in a lineup of journalists for an interview can take a withering toll on the sturdiest of egos, so I appreciated the effort. “I like your dress!” I said, and Portman said, “Thanks,” for likely the twentieth time that day.

Save media interest, there is no actual parallel between a movie star sitting through a press day to promote her Oscar chances and the first lady of the United States bearing the onslaught of the world’s attention in the wake of her husband’s assassination. But Jackie, Pablo Larraín’s shockingly close-range film, which focuses on Jackie Kennedy (literally: her face is the focus of most scenes) in the days just after Dallas, is about much more than one iconic woman’s feelings. It’s about the way that narratives are shaped. It’s about writing history as you would have it remembered. It’s about controlling image, and how images are projected to the public.

And that’s something that Portman—and her publicists, tapping on their phones just out of eyeshot but certainly not earshot—knows something about. The actress (and producer and director) is known for being extremely private, and aside from a somewhat infamous email dialogue between herself and Jonathan Safran Foer published this summer in the New York Times, her efforts have been effective.

Anyway, we set out to discuss the ways that Jackie is relevant now. (“A first lady taking the reigns of the situation is of course resonant now, but also, while the definition of a woman through her husband’s actions is sort of this outdated mode—it’s still very much around, in how we see women.”) Then, I’m curious whether she thinks the requirements for serious films are changing; is it enough to just have great performances and great stories, or is there a more pressing emphasis on reflecting and confronting the embattled “issues” of the times? She says she’d need to think about it more. (“I mean, I feel like there have always been movies that resonate because of what’s going on, and then movies that resonate because they’re timeless.”) She seems to be getting sleepier and I consider calling it quits for both of us. There’s a room with vats of coffee and small mountains of pastries just down the hall.

“So I used to have this dream about you,” I say.

She perks up a bit, probably her fight or flight kicking in.

“Well, maybe better to say, I used to have this recurring dream and you were in it. It wasn’t about you.” We laugh, and a joke is made in the “I guess everything can’t be” vein.

I explain: I had the dream my senior year of college, the year that Black Swan came out and Portman won Best Actress for it. The movie was a minor obsession among my friends, and our house was littered with black feathers for months after Halloween. We took a beginners ballet class. I’d been dating the same guy for years, but I was beginning to have these wedding nightmares. In the dream, I’d get halfway down the aisle, look around at all the people around me—friends, family, smiling expectantly—and just turn and run. The rest of the dream mostly consisted of handling highly mundane details in the aftermath of this decision (trying to get refunds for honeymoon reservations, figuring out what shelter to give the catered food—the real gruesome stuff). But the one other piece of the dream was that, inexplicably, Natalie Portman was always there among the guests, my second cousin. And my dad would always say, “Look what you’ve done! Your cousin Natalie the movie star made time in her busy schedule to come to your wedding!” And that was the guilt cherry on the horror Sunday of my wedding nightmare.

Portman laughs very generously.

“But I sort of have a point,” I say. “I’m curious what it’s like to be so famous that you are embedded into the consciousness—the dreams, even—of people you’ll never even know.”

“Well,” she says, “I don’t think I see it much personally. Although, obviously, you know that people have ideas about you. But I think even people who aren’t necessarily in the public eye get that now because of social media. There could be someone in your college class that you don’t know who looks at you a certain way, and thinks certain things about you, and might write about you, or whatever. And you’re not a famous person—you’re just being talked about or thought about in a certain way by someone you don’t know. So you know, it’s something we all have to deal with on different levels. I mainly try to not think about it. Like, I don’t look at it; I don’t seek it out in any way because I don’t find it helpful in any way.”

“But…” she pauses. “Fame does create a splitting of the self, I suppose. Because you’re, like, aware that this is the part of me that’s public, and this is the part of me that’s private, and so you’re kind of dividing the two. Jackie obviously had that on a much larger scale, but it was definitely something that I could see in her and empathize with—that there is an idea of how other people see you, an idea of who you really are, who you want other people to think you are. And there is how you think you’re supposed to be. There are all these different layers of self.”

There’s a reason that Larraín said of Portman, “I couldn’t imagine a movie without her.” I’d have to agree. Portman’s performance in Jackie is shattering, and the layering of the self is integral to the character she draws up around her—a woman who repurposed the legend of Camelot to forever shade our nation’s memory of her husband’s presidency with a hue of mythical potential. We see that her dignified theatrics were born from a deep reserve of decorum; sorrow and anger and determination bubbled to the surface with frenetic energy. She recognized the urgency of seizing the moment, when history was still an unformed blob of grief and shock, to meld the formless, hopeless narrative into an ironclad enshrining. And Portman’s Jackie is as we’ve never seen her before. She will imprint on our dreams all over again.

“It’s such an unusual thing when someone is so well known and yet not known at all,” Portman says. “That someone can be so two dimensional in the way we know them, iconographically. This film explored that. You really do see that Jackie was at a moment where she defined herself through her husband—really took her identity as his wife—but was authoring her own story by creating his legacy. And that’s what everyone does now, showing the public what they want to see—on social media or whatever. But she did that back then. She was already saying, ‘I’m going to be the author of this story. Not a journalist, not a historian.’ And that’s so modern.”

It’s true: Jackie was a harbinger of the world we inhabit now. And in the film, as I watched her give her side of the story to a journalist—speaking candidly while reminding him it’s off the record—rendering him little more than a scribe to her magnum opus, I thought, well, this is a silver lining for Jackie. Portman’s publicist comes in and taps his watch; my 15 minutes are up.