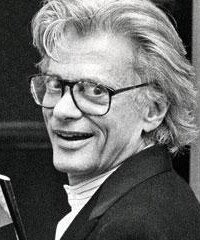

Some people called him a “wonderful terrible mirror.” Others said he was exploitative and manipulative. But that’s really beside the point. Richard Avedon was one of the greatest photographers in the world, both in fashion and portraiture. He died in 2004 at the age of 81, and his work is being shown as much as it ever was in museums and galleries across the globe. This past May his exhibit of epic-size photographic murals at the Gagosian Gallery in New York City was so popular, it had to be extended. Some of the subjects were emblematic cultural figures like Andy Warhol, and others were groups of government officials who participated in the Vietnam War juxtaposed with victims of the war—survivors of napalm attacks.

These studies were the work of Avedon’s life and what he wanted to be remembered for. But he may be best known for the endless stream of magical pictures that appeared in Harper’s Bazaar from 1944 to 1965 and then in Vogue, where he was on staff until 1988. In those pages he revolutionized fashion photography by directing his models to dance and leap and twirl and stride about in their boxy coats and swishy silken ball gowns. “You are women enjoying yourselves,” he would say.

Avedon’s work has been described as “snapshot realism”—fashion in motion where the models, clothes, makeup and hairstyles blur gorgeously and you somehow get a sense of the freedom and energy that is America. He became rich and celebrated, but he disliked being known as simply a fashion photographer. Especially because he had always challenged himself by doing reportage, documenting New York City’s streets and taking celebrity portraits. He worked with a Rolleiflex but eventually switched to an old-fashioned 8-by-10-inch Deardorff camera, “because I no longer wanted to hide behind the camera. I wanted nothing to help the photograph except what I could draw out of the sitter.”

His initial attempts were soft, worshipful pictures of Henry Fonda as Mister Roberts and Mary Martin in South Pacific. But by 1958, Avedon had grown bolder. He photographed a hungover Dorothy Parker; a befuddled President Eisenhower; a manic Charlie Chaplin; an eccentric, hairy Ezra Pound shrieking into the lens.

Then there was the ravaged close-up of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Avedon had arrived at their Waldorf Towers apartment in New York City and began setting up his cameras as the royal couple carefully arranged themselves. “I’m sorry I was late,” Avedon told them, “but the most terrible thing happened. My cab ran over a dog.” (It wasn’t true.) The Windsors, both dog lovers, gasped, “Ah!”

Click went the shutter. An iconic photograph was born.

For years Avedon had lived with his family on Park Avenue and worked out of a studio on East 58th Street. In 1970 he decided to move to a place where he could live by himself and work 24 hours a day if he wanted to.

He bought a house on East 75th Street and renovated it. He put in a huge, white-walled studio on the first floor, a darkroom in the basement; he built a terrace garden on the second floor. Avedon then began to work as he had never worked before on his mammoth personal projects, the photographic murals that would reflect the changing times and the people who changed them, in the civil rights movement, the counterculture and the Vietnam War.

Recently I paid a visit to Avedon’s house. The rooms where the photographer worked have been carefully preserved. The darkroom and studio are intact; the shape and structure of the house are still the same—superbly designed, everywhere stark white walls with black stairs. It’s a knowing tribute to Avedon’s minimalist style.

The impressive six-bedroom, nine-bath residence is complete with a gym in the basement. When this is combined with the remaining areas of the house, it adds up to 8,475 square feet of glorious light-filled space. The highlights for me were the two outdoor terraces. Landscape designer Miranda Brooks transformed them into leafy green sanctuaries with cherry trees and boxwood hedges.

Before I left, I walked through this remarkable dwelling again and came to Avedon’s studio, so immaculate and white, where he photographed everyone from Hillary Clinton to Philip Seymour Hoffman. I was reminded of how he always wanted his photographs printed on gleaming white semigloss or matte simulacrum to make the subjects stand out with hallucinatory sharpness.

“There, all is only order and beauty, luxury, calm and pleasure,” Baudelaire wrote of one fabled place he adored. The same could be said of this new version of the house of Avedon, which the photographer’s spirit still inhabits.